Foreword

We congratulate Cabo Verde and Egypt on being certified by the World Health Organization as being malaria-free. This accomplishment is a reminder to all that—with sufficient political will, multisectoral advocacy and action, deployment of new tools and sufficient resources—we can end malaria.

Yet, as we stand at the crossroads of Africa’s battle against malaria, progress in most Member States remains stalled. The interim targets for 2025 are slipping out of reach, and the dream of eliminating malaria by 2030 is in jeopardy. Now is the moment to confront a hard truth: we are not on track and we face a perfect storm of threats — insufficient resources, rapid population growth, climate change, biological risks and humanitarian crises.

2025 is a make-or-break year. The Global Fund replenishment in 2025 will determine whether we sustain the progress that has been made or fall further behind. It is imperative that we secure the resources necessary to combat malaria with renewed energy. Africa must also rise to the challenge by mobilising domestic resources, scaling innovative financing through End Malaria Councils and Funds, and leveraging platforms like IDA and the Green Climate Fund to ensure that our national programs are fully equipped to drive the malaria agenda forward.

Strategic data must guide our decisions so that the most impactful packages of interventions are tailored sub nationally to maximise impact. Scorecard Tools can strengthen accountability and action at all levels and help ensure that our commitments are realised.

New interventions and commodities must be fast tracked and rapidly scaled up. This includes rolling out the next generation commodities (e.g., the highly impactful dual insecticide nets and insecticides) and accelerating the malaria vaccine so that it is deployed alongside existing tools. The pipeline of new malaria tools and interventions has never been better, can be manufactured on the continent to drive economic growth and development, and will help accelerate malaria elimination.

Multisectoral action is critical including coordinated efforts across sectors—agriculture, education, environment, local government, infrastructure, to create a holistic response to malaria elimination.

We must embrace an integration agenda that addresses malaria alongside other critical priorities: primary health care, pandemic preparedness, gender equity, and climate resilience. These issues are central to creating resilient health systems and sustainable development. Malaria not only devastates health but also imposes a significant economic burden on Member States. In malaria-endemic regions, the disease reduces GDP growth by up to 1.3% annually and is responsible for up to half a billion lost workdays in Africa each year. Investing in malaria elimination offers substantial economic returns. A recent study shows that eliminating malaria could increase GDP by $127 billion across Africa by 2030. International trade would also benefit, with potential gains of $81 billion through improved market access, consumer demand, and enhanced business opportunities. Importantly, long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs)—costing just $4.89 per unit—offer an exceptional benefit-cost ratio (BCR) of 9.8 to 1, saving lives and yielding enormous returns by reducing treatment costs and averted deaths. Overall, defeating malaria by 2030 could yield a 40 to 1 return on investment, making it one of the highest-impact investments in global health.

Leaders, policymakers, and partners—this is our call to action. Our response must be bold and decisive. We must unleash a “Big Push” that enhances political commitment and multisectoral engagement, resource mobilisation, ensuring that available resources are targeted to maximise impact, and fostering the rapid introduction of new, fit-for-purpose tools to fight malaria. The stakes could not be higher. Africa’s future demands that we step up, invest, and recommit to ending malaria once and for all. The world is watching, and history will remember how we acted at this pivotal moment. The time for hesitation is over. Now is the time to act with unity, urgency, and unwavering resolve.

H.E. Moussa Faki

Chairperson

African Union Commission

H.E. Umaro Sissoco Embaló

President

Republic of Guinea-Bissau

Dr. Michael Charles

Chief Executive Officer

RBM Partnership to End Malaria

Progress towards Eliminating Malaria in Africa by 2030

Africa remains the epicentre of the fight against malaria

According to the WHO, there were an estimated 251 million malaria cases (95% of global cases) and 579,414 malaria deaths (97% of global deaths) in African Union Member States in 2023. 76% of these deaths were children under the age of five. Across the continent, 1.3 billion individuals are at risk of malaria infection. Amongst this population, there were 192 cases per 1,000 persons and 44 deaths per 100,000 persons. Compared to 2000, this represents a 34% reduction in malaria incidence and 61% reduction in malaria mortality.1

Member States have continued to rapidly scale the distribution of next-generation nets (78% of the 195 million nets distributed in 2023 compared to 59% in 2022). Likewise, a record 53 million children under the age of 5 received SMC, including 28.6 million in Nigeria alone. Cote d’Ivoire and Madagascar introduced SMC for the first time in 2023.

Cabo Verde and Egypt were certified by the World Health Organization as having eliminated malaria in 2024.2

Most Member States are not on-track to achieve the AU target for eliminating malaria by 2030

Progress remains stalled, and the continent is not on track to achieve its goal of controlling and eliminating malaria by 2030. The AU’s Catalytic Framework3 set targets for reducing malaria incidence and mortality to achieve malaria elimination across the continent by 2030. However, malaria incidence has declined only by 4% and mortality has decreased by 15% since 2015, well short of the AU’s interim targets of 40% by 2020 and 75% by 2025. Of the 46 Member States reporting incidence of malaria, only six have achieved a 40% reduction in incidence and seven in malaria mortality.4

A “Perfect Storm” threatens progress

The fight against malaria faces a perfect storm of converging crises that threaten to derail decades of progress against the disease. Member States face serious funding gaps linked to the ongoing financial crises and declining donor resources, increasing levels of biological resistance, including drug and insecticide resistance, adverse effects of climate change and humanitarian crises, invasive mosquitoes that threaten to increase urban malaria transmission, and a rapidly growing population at risk of malaria.

Funding Gaps

Globally, malaria funding continues to fall short of levels needed to eliminate the disease. Of the $8.3 billion target in 2023, only $4 billion has been invested. This gap is rapidly expanding, increasing from $2.9 billion in 2019 to $4.3 billion in 2023.

Member States express concerns about resource gaps and continued reliance on external donors. An additional $1.5 billion is needed to maintain existing (but insufficient) malaria intervention coverage in 2025-2026.5 Not only do the existing gaps in coverage need to be addressed urgently, but increased funding is also needed to scale up coverage and roll out highly effective yet more expensive commodities to address biological resistance. WHO estimates that an additional U$6.3 billion is needed annually by 2025 to achieve global targets. If there is a continued flatlining of malaria resources over 2027-2029, there will be an estimated additional 112 million cases and up to 280,700 additional malaria deaths in Africa as a result of upsurges and outbreaks across the continent.6,7

A small number of external donors continue to provide the majority of financing for malaria interventions. Member States highlight the risk this presents to long-term sustainability and a need to diversify sources of funding.

Humanitarian emergencies

Malaria is concentrated in countries impacted by humanitarian crises. In 2023, an estimated 74 million individuals were either internally displaced or refugees. Population displacements, disruptions to supply chains and health service delivery can contribute to significant increases in malaria cases and deaths. Humanitarian crises also lead to significant increases in delivery and implementation costs, further exacerbating funding gaps. Member States express particular concern about the lack of resources to provide malaria interventions to populations displaced across borders and the need to strengthen planning to serve these vulnerable groups.

Biological threats

Insecticide resistance is widespread, reducing the efficacy of traditional mosquito nets and indoor residual spraying at preventing malaria transmission. The malaria parasite is also increasingly resistant to diagnostic tests and antimalarial medicines, affecting case detection and management. 8 Member States have reported confirmed or suspected partial antimalarial drug resistance. New, highly effective tools are available to address these threats, but they are more expensive than the traditional tools.8

Likewise, Anopheles stephensi, an invasive mosquito which has been detected in 8 Member States.9 This mosquito can thrive in urban areas, increasing the threat of malaria transmission and upsurges in rapidly growing population centres and hubs for economic development.

Climate change

A warmer and wetter climate accelerates the development of mosquitoes and transmission of malaria, including in areas that currently have a low burden. Already, the number of months suitable for malaria transmission in Africa’s highlands has increased by 14%.10 By the 2030s, an estimated 147-171 million additional Africans will be at risk of malaria.11 An estimated 775,000 excess malaria deaths are anticipated by 2050 in regions where climate change is driving increased transmission.12

Short-term extreme weather events are causing large spikes in malaria. Displaced populations are often unprotected by nets or indoor residual spraying and have limited access to diagnosis and early treatment. Even in countries where malaria deaths might decrease due to changes in temperature and moisture, extreme weather events attributable to climate change are expected to cause an additional 230,000 malaria deaths (primarily in West Africa, Sudan, South Sudan, Mozambique).13

Increasing Population at Risk of Malaria

An anticipated growth of 16.5% is expected in the population-at-risk of malaria by 2030, significantly increasing the number of malaria cases and the costs of sustaining and scaling up interventions.

An acceleration plan is needed to translate political commitments into action

To address these threats and achieve the goal of eliminating malaria in Africa by 2030, the AUC, RECs, and Member States need to develop an acceleration plan that translates the political commitments and decisions of the ALMA Heads of State and Government into increased funding, action, and accountability.

The AU Roadmap to 2030

The AU Assembly tasked the AU Commission, AUDA-NEPAD and Africa CDC to develop a comprehensive and fully costed AU Roadmap to 2030 and Beyond as a guideline for strengthening health systems, improving access to healthcare, reducing maternal deaths, and overcoming endemic diseases including malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases. The roadmap follows a series of key decisions and commitments made by the AU and reflects the AU’s resolve to advance health security and development in Africa, create a healthier, more resilient Africa in which every citizen is healthy and well nourished. The Roadmap focuses on ending AIDS, TB, Malaria and improving maternal health, addressing endemic non-communicable and neglected tropical diseases and conditions in Africa by 2030. The Roadmap will galvanise political advocacy and resource mobilisation; encourage governments to take a people-centred, rights-based approach, champion science, mobilise political, domestic and financial support, and strengthen national capacities to end inequalities.

Acceleration Priorities

1. Strengthen Political Will & Leadership

Member States are encouraged to convene senior leaders across all ministries to develop a whole-of-government approach to create an enabling environment for the implementation of the national malaria strategic plan. This approach must also ensure that there are sufficient resources to fully implement universal access to life-saving malaria interventions.

Sustained political leadership is critical for keeping malaria high on national development agendas. This involves heads of state and government and other senior leaders championing malaria elimination, advocating for resources, and supporting the integration of malaria goals into broader national, regional and continental development plans.

Heads of State & Government

Heads of State and Government can ensure that malaria is regularly discussed in cabinet and other high-level forums, convene senior leaders across all sectors (e.g., via an End Malaria Council) and lead advocacy at the global, regional and national levels (e.g., support the replenishment of the Global Fund).

Benin: H.E. President Patrice Talon issued a decree to revitalise the national HIV/AIDS Council to include TB and malaria and call on multisectoral collaboration across line ministries.

Government Ministers

In 2024, Ministers of Health from the High Burden to High Impact countries in Africa adopted the Yaoundé Declaration. This declaration reflects a strong commitment to accelerating the reduction of malaria mortality. It provides a comprehensive framework built around seven pillars to address the key challenges impeding progress. The Yaoundé Declaration—which builds on existing initiatives such as the “Zero Malaria Starts with Me!” campaign and the High Burden High Impact approach—provides a framework for developing a malaria acceleration plan.

Nigeria: The Minister of Health convened multisectoral stakeholders and partners to develop an innovative strategy for accelerating progress against malaria. This resulted in a nine-point plan with working groups developing strategies for each (e.g., resource mobilisation, interventions).

Ministries and parastatals beyond health can contribute to the fight against malaria by proactively identifying actions and policies within their areas of focus.

Burkina Faso: The Ministry of Youth has recruited 15,000 national volunteers/community health workers and made them available to the Ministry of Health.

Cameroon: The permanent secretaries from multiple line ministries (e.g., education, agriculture) agreed to undertake activities that reduce malaria and include them in their ministries’ budgets.

Nigeria: The Ministry of Environment allocated funding to support disease control and is working with rice farmers to reduce mosquito breeding and malaria transmission.

Uganda: Malaria control is now listed as a cross-cutting issue prioritised for funding in ministerial budgets. The 2024/2025 budget allocated an additional UGX139 billion ($40 million) for essential medicines and health supplies, including 5 billion UGX ($1.4 million) for medicines to prevent malaria in pregnant women.

Tanzania: A structure for public sector coordination was established under the Prime Minister’s office to support the End Malaria Council. Malaria focal points from each line ministry were appointed and trained on the national scorecard, priority interventions, and gaps.

Parliamentarians

Parliamentarians play a pivotal role in the fight against malaria by shaping policies, securing budget allocations, and ensuring accountability for malaria programmes. They advocate for legislation that supports malaria elimination efforts and ensure that malaria remains a national priority in development agendas. Parliamentarians also have the power to allocate and sustain funding for malaria and health interventions in national budgets. Additionally, they engage in advocacy both within their constituencies and internationally, raising awareness of malaria’s impact and mobilising community action.

Cameroon: Parliamentary caucus advocates to ministers, meets regularly with the Prime Minister to discuss malaria elimination, and supported resource mobilisation to purchase nets.

Ghana: Parliamentary caucus advocated for increased funding, resulting in budget allocation for IRS.

Nigeria: The Chair of the House Committee on HIV, TB and Malaria (an End Malaria Council Member) introduced legislation calling for increased funding for malaria and universal accessibility of malaria commodities.

Senegal: Established a parliamentary network on malaria, including training on malaria and NTDs. Advocacy by parliamentarians resulted in the government purchasing preventative medicines previously donated by partners.

Tanzania: Parliamentarians meet regularly with the NMCP to discuss malaria issues and actively monitoring malaria interventions through malaria scorecards.

Uganda: The Uganda Parliamentary Forum for Malaria provided oversight and community mobilisation for IRS in high-burden regions and support decentralisation, reducing costs and increasing impact.

Subnational Leaders

Governors, mayors, and other local leaders are trusted messengers for distributing malaria messages, convening community dialogues, and working with local stakeholders to drive accountability and action on health.

Senegal: The NMCP has entered into a co-financing agreement with municipalities to support malaria interventions.

2. Mobilise sufficient and sustainable resources

Member States are encouraged to increase resources for malaria by leveraging broader and more diverse funding sources.

The economic case for investing in malaria control and elimination is clear. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goal malaria targets by 2030 could boost the GDP of malaria-endemic countries in Africa by $126.9 billion, with global benefits including an $80.7 billion increase in international trade.14 This economic dividend underscores the necessity of financing our fight against malaria—not just to save lives, but to drive economic growth and development across the continent.

Despite the investment case, Member States continue to face significant resource gaps with only half of activities in national malaria strategies being funded. There is a need to secure US$6.3 billion annually to sustain and expand malaria elimination efforts. Likewise, the continued reliance on a small set of funders presents a threat to long-term sustainability.

The Global Fund & GAVI

Member States must strongly advocate to global partners and support the replenishments to close immediate financing gaps. 2025 is a make-or-break year for malaria financing with both The Global Fund and GAVI undergoing replenishments. A shortfall will result in further financial strains on national malaria programmes.

- The Global Fund provides more than 40% of malaria elimination funding and 62% of all international financing for malaria.15

- GAVI is essential to continuing the roll out of the malaria vaccines.

Successful replenishments are not only essential for malaria elimination but also for strengthening overall health systems and addressing other health challenges (e.g., NTDs).

Development Bank Financing

Member States are integrating malaria into broader development initiatives, such as climate change, health systems strengthening, and pandemic preparedness and response, as well as development bank funding priorities and work (e.g., World Bank International Development Association).

Nigeria: Several states are rolling out interventions financed by loans from the World Bank and Islamic Development Bank.

Malawi: Integrated malaria interventions into its funding application to the Green Climate Fund.

Domestic Funding

Member States are encouraged to allocate increased funding for health and malaria in the national budget, in line with existing targets and commitments (e.g., Abuja Declaration). Increased domestic spending on health promotes long-term sustainability of health systems.

Benin: The Government has made a 28.5% increase in the 2025 malaria budget compared to 2024. This follows a 140% increase from 2022-2023 and a 20% increase from 2023-2024.

Burkina Faso: The government has maintained the health budget at more than 13% of the state budget, and an additional budget of 5 billion XOF has been allocated for the expansion of the malaria vaccine.

Mauritania: The Government is committed to increase financing for malaria by covering 40% of the cost of malaria commodities (RDT, ACTs) and 100% of severe malaria treatment.

The private sector plays a critical role in the fight against malaria by providing financial and in-kind resources, driving innovation, and leveraging their expertise to support malaria programs. Companies contribute through in-kind contributions, direct investment and corporate social responsibility funding, as well as providing technical expertise and logistical support to national malaria programmes. The private sector can contribute significantly towards innovation and improving the capabilities of malaria programmes, especially in areas like supply chain management, advertising and communications campaigns, and community engagement, enhancing efficiency and strengthening public-private partnerships.

Burkina Faso: The ‘Zero Malaria ! Businesses Get Involved’ initiative, supported by Speak Up Africa, mobilised resources with the Ecobank Foundation. The Endeavour Mining Foundation funded the implementation of the ‘Malaria-Free Village’ project.

Benin: Canal+ Benin signed an MoU committing to contributing to malaria control efforts and made an initial contribution of 500 mosquito nets to support routine distribution for women and children in the Allada district.

Senegal: Construction company ICONS is implementing a malaria action plan for 2024 estimated at $65,000. Microfinancing company ACEP is implementing a plan estimated at $27,000. Canal+ Senegal continued to support efforts through the free broadcasting of an awareness raising video for the duration of the rainy season, as well as buying bicycles for community health workers.

End Malaria Councils & Funds (EMCs)

The ALMA Heads of State and Government have called on Member States to establish national EMCs to facilitate mobilising, pooling, and distributing resources from new donors and the private sector. As of 2024, 9 Member States have launched and 4 have announced EMCs. Member States are encouraged to accelerate the establishment of EMC.

These county-owned and country-led forums are composed of senior leaders from government, the private sector, and civil society. These leaders collaborate to advocate for malaria to remain a top priority on national development agendas, mobilise resources, and ensure accountability for achieving targets in national malaria strategic plans. EMCs address operational bottlenecks and resource gaps by using their influence, networks, and expertise to mobilise commitments from all sectors and then monitor and report on progress during quarterly meetings.

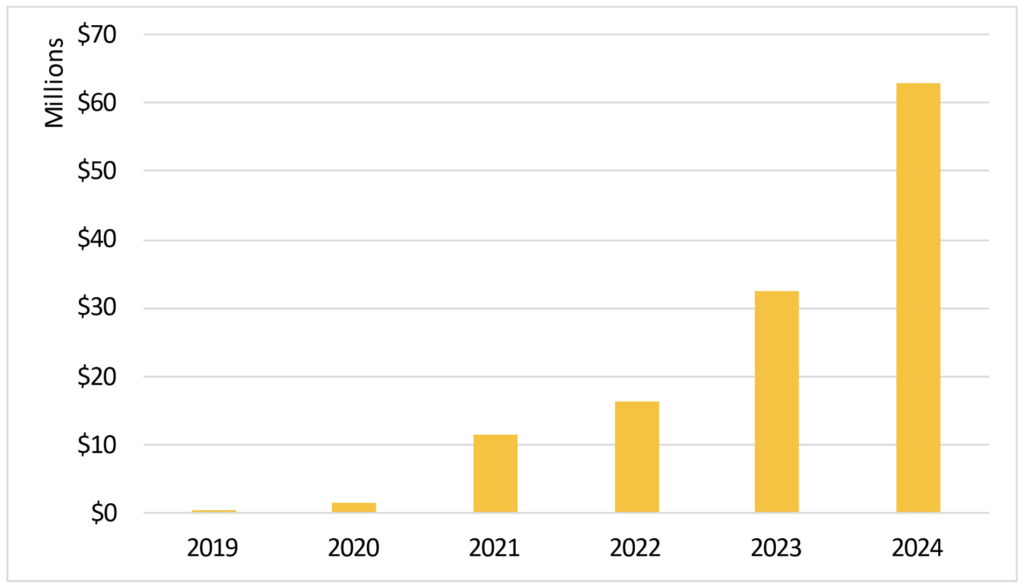

EMCs have collectively mobilised more than $125 million USD ($62 million USD in 2024) in financial and in-kind support and technical expertise.

Resources Mobilised by EMCs by Year

This funding has strengthened malaria control efforts, allowing countries to scale up interventions, address funding gaps, and raise the visibility of malaria through national and community advocacy and communications campaigns. Several EMCs are also pursuing initiatives to increase local manufacturing of commodities.

Mozambique: Following a pledge to the national End Malaria Fund, Kenmare invests in implementing malaria interventions to protect employees and their families against the threat of malaria.

Tanzania: The Mining Sector has proposed $1.5 million in CSR commitments to support malaria interventions in districts where they have operations.

Uganda: NextMedia continues to collaborate with the National Malaria Control Division and Malaria Free Uganda (an EMC) to disseminate malaria messaging on national television and social media.

Zambia: The private sector and traditional leaders on the End Malaria Council are launching malaria enterprises that will promote malaria awareness and create sustainable sources of funding for malaria interventions. The EMC worked with the NMCP to mobilise $11.2 million to procure nets and $12 million from Rotarians to support community health workers.

EMCs also support multisectoral coordination and advocacy with national and community leaders (e.g., religious and traditional leaders).

Nigeria: The Federation of Muslim Women’s Associations in Nigeria (FOMWAN) has produced radio advertisements and advocacy materials that have been distributed to empower religious leaders and women to take action to address malaria.

Tanzania: Religious leaders organised national advocacy and communications campaigns for World Malaria Day, including a bike race.

Zambia: The Faith Leaders Advocating for Malaria Elimination (FLAME), a member of the EMC, continues to implement national advocacy and resource mobilisation campaigns, including using the scorecard.

Resources and toolkits on how to establish an EMC are available online at https://scorecardhub.org/emc/

3. Enhance Multisectoral Coordination and Action

Member States are encouraged to pursue whole-of-society approaches to combat malaria.

Countries that have successfully eliminated malaria, such as Cabo Verde and Egypt have demonstrated that multisectoral collaboration and coordination are critical to driving advocacy, strengthening national coordination, building expertise, and mobilising additional resources.

Youth

Member States launching national Malaria and NTD Youth Corps to engage young people in the fight against malaria, NTDs and in advancing Universal Health Coverage (UHC). These coalitions of youth leaders support the work of malaria and NTD programmes. A total of 16 youth corps have launched in Member States. These youth corps were involved in key activities with NMCPs such as supporting the delivery of mosquito net distribution, IRS, SMC, scorecard training, and other activities.

Burkina Faso: The Malaria Youth Corps, which launched on World Malaria Day 2024, is raising awareness in their communities about the necessity of identifying and destroying larval habitats. Youth hare also supporting school-based training initiatives.

Chad: Convened a network of youth to support community sensitisation and dissemination of malaria messaging.

Kenya: Malaria Youth Corps has engaged senior political leaders to sustain high-level commitments.

Nigeria: Youth are being empowered to support the deployment of interventions.

Senegal: Youth champions have been engaged through the Ministries of Health and the Ministry of Youth, Employment and Citizen Building to promote malaria messaging and care for pregnant women.

Uganda: The National Malaria Youth Champions conducted a visit to Iganga district, where they used the scorecard to identify key drivers of poor performance for malaria in pregnancy (e.g., low awareness and misconceptions about IPTp) and provided health education to pregnant women.

Religious Leaders

Religious leaders play a vital role in the fight against malaria by leveraging their influence and trusted status within communities to promote malaria prevention and treatment. Through sermons, community gatherings, and faith-based networks, they raise awareness about the importance of using bed nets, seeking timely diagnosis, and adhering to treatment protocols. Religious leaders also serve as advocates, engaging policymakers and mobilising community-level action. Their moral authority helps reduce stigma, encourage healthy behaviours, and support national malaria campaigns, making them key partners in the drive to eliminate malaria.

Burkina Faso: The Union of Religious and Traditional Leaders has mobilised blood donations to support cases of severe malaria that require a blood transfusion; disseminate social and behaviour change communications.

Civil Society

Civil society organisations (CSOs) play a pivotal role in malaria control and elimination efforts, particularly in advocating for the most vulnerable populations, including women, children, and rural communities. These organisations work to ensure that malaria prevention, treatment, and control measures reach those disproportionately affected by the disease. CSOs raise awareness about the dangers of malaria, advocate for policy changes, and push for increased funding to support malaria interventions targeted at these vulnerable groups.

CSOs also lead campaigns to empower women, who are often the primary caregivers, to take a leadership role in the fight against malaria. By amplifying the voices of affected communities, particularly children and women, civil society organisations ensure that their needs are represented in national and global malaria policies.

Burkina Faso: The Network for Access to Essential Medicines (RAME) plays a monitoring role in the quality of the service offered to users and the availability of malaria treatment and prevention materials at all levels of the healthcare system.

Women representatives participate in the national CCMS to ensure that funding priorities account for gender.

4. Strengthen National Health Systems

Member States are encouraged to invest in strengthening health systems to improve the delivery of malaria prevention and case management, including as a pathfinder for primary health care, key elements of pandemic preparedness and response, and the intersection of climate change and health.

Integration of malaria interventions into routine services

Malaria service delivery is already integrated into antenatal care (ANC), EPI and community case management. For example, interventions to protect pregnant women are largely managed through antenatal care visits to health facilities (i.e., IPTp, ITNs, and case management). Further integration, as well as closer ties with community health workers, will help to fill the current gap between IPTp and ANC coverage. The malaria vaccine and Insecticide Treated Nets are delivered through the immunisation programme.

Burkina Faso: Malaria vaccination and seasonal chemoprevention campaigns increase reach of overall vaccination programmes and result in increased visits to health facilities.

Malawi: Introduction of the malaria vaccine has strengthened EPI by increasing supervision of vaccinations more broadly, reducing gaps and improving programme quality.

Uganda: Investment in malaria surveillance has increased laboratory capacity, training of staff and procurement of equipment;SMC platform helps identify and track children that are not immunised, especially those in vulnerable and hard-to-reach regions.

Investments in surveillance, school-based initiatives, mass drug administration, and other activities can yield benefits for efforts to control and eliminate other vector-borne diseases—including Neglected Tropical Diseases NTDs).

Integrated Community Case Management

Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) is a cornerstone of the malaria response. Increasing investments in community health programmes, including iCCM approaches, can enhance capacity to address malaria alongside other key issues affecting maternal health, gender equity, and childhood killers such as pneumonia and simultaneously builds resilience to the shock of health security threats such as COVID 19. Rural community health services which include malaria case management, are embedded in local communities to meet their priority needs, extending health services to communities that do not have easy access to health facilities whilst also responding to epidemic and pandemic threats before they spread. Malaria programmes design and implement interventions that penetrate hard-to-reach and often marginalised rural communities, as part of integrated health service delivery. Similarly, the procurement and supply chain that delivers essential malaria commodities to both health facilities and remote communities have beneficial impact across the whole health system, strengthening the health system supply chain.

Malawi: Uses iCCM to trace children who have been discharged after recovering from severe malaria or severe anemia and provide monthly preventative treatment in community clinics.

Burkina Faso: Implementing a contingency plan for HIV, Tuberculosis, and malaria, which allows the continuation of health services for the benefit of the population in high-security challenge areas. It delegates responsibilities to community stakeholders to facilitate the supply of inputs up to the last mile.

Climate Change and Health

Member States’s ability to respond to climate disasters is limited by the lack of additional resources (i.e., human, infrastructure, logistics and financial) and the long lead time to procure malaria commodities. Vulnerable women and children, who account for 80% of global malaria deaths, will be the face of this looming catastrophe. Malaria offers “the opportunity-driven lens” that was called for at the 2023 Africa Climate Summit. Malaria is an ideal candidate to contribute to Disaster Risk Knowledge & Management and Preparedness & Response Capabilities of the “Early Warning for All – African Action Plan.” Member States are working to integrate malaria and climate change into their planning and emergency response. This includes assessing the availability of malaria commodities to be deployed following a natural disaster (e.g., a cyclone that destroys health facilities and ruins vector control interventions). Many existing interventions have long procurement timelines resulting in a growing need to pre-position buffer stocks. Local manufacturing of malaria commodities may also shorten supply chains, enabling a more rapid response to climate emergencies.

Senegal: Integrated climate planningfor displaced populations into operational plans (e.g., procuring additional buffer stock) and the military worked with the Ministry of Health to distribute mosquito nets after widespread flooding.

Nigeria: Contained the impact of flooding in 2 states by redistributing commodities from other states.

There is also an opportunity for the malaria community to lead by example by ensuring that local manufacturing initiatives are driven by clean energy. The health sector must also push towards zero carbon emissions for manufacturing, health facilities and institutions (public and private), and commodity supply chains (including the cold chain).

5. Adopt the Latest Guidance

Member States are encouraged to continue fast-tracking the adoption and dissemination of the latest technical guidance on malaria control and elimination.

There is a need to continue rapidly scaling up the deployment of new and more effective malaria interventions to accelerate progress. This includes new interventions such as next-generation vector control methods, vaccines, and diagnostics, while also addressing emerging challenges like resistance to drugs and insecticides.

Addressing insecticide and drug resistance

The WHO has issued updated guidance on case management and vector control (e.g., the comparative efficacy of new products) ensuring that countries have the best tools for controlling mosquito populations.16 Member States have responded by significantly increasing the use of chlorfenapyr-treated mosquito nets and rolling out malaria vaccines.

Member States are also working to introduce multiple first-line therapies to address resistance.

Burkina Faso: Introduced multiple first line therapies includingArtemether Lumefantrine, artesunate + pyronaridine, and dihydroartemisinin + piperaquine in 2024. Additionally, taking advantage of the seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) campaign, the identification and destruction of larval habitats inside homes was integrated in collaboration with the residents of each concession. This has improved the populations’ knowledge about the link between larvae and mosquitoes and the necessity to destroy them.

Tanzania: Due to Artemisinin Partial Resistance, the country is considering to transition their drug policy from AL to ASAQ , starting with regions most affected by resistance. To facilitate this change, a Transition Task Team is being established which will develop a comprehensive transition timeline, estimating costs, strategies to mitigate resistance, and prepare a roadmap for the potential adoption of Multiple First-Line Therapies.

Roll Out of Malaria Vaccines

The WHO released new guidance on the use of malaria vaccines, including updated recommendations for the RTS,S/AS01 and R21/Matrix-M vaccines.17 These vaccines are now prioritised for use in areas with moderate to high transmission of malaria, particularly in children. 15 Member States are rolling out two malaria vaccines as part of their immunisation programmes and aim to protect 6.6 million children over the next two years across Africa, with support from Gavi, WHO, and UNICEF.18 Several Member States also report increased use of chemoprevention, including in high-burden districts, as part of elimination strategies, and in the preventative treatment of school children.

Burkina Faso: Introduced the malaria vaccine into the routine Expanded Program on Immunisation in 27 out of 70 health districts. Through September 2024, coverage is 87%, 77%, and 68% respectively for the first, second, and third doses. Catch-up strategies are being implemented and the door-to-door malaria chemoprevention campaign is an opportunity to identify insufficiently vaccinated children.

6. Use Strategic Information for Action

Member States are encouraged to continue strengthening the use of health data and information systems to guide decision-making. This includes using real-time data to drive action.

Subnational Stratification and Tailoring

Member States are implementing subnational stratification and tailoring the packages of interventions based on the subnational malaria burden. This optimisation enables countries to maximise the impact of available resources, especially when there are funding gaps. Member States are also enhancing their existing scorecard tools to monitor the progress and effectiveness of targeted intervention packages.

Burkina Faso: Uses stratification to identify districts for the extension of the SMC to children aged 5 to 9 years.

Ethiopia: Identified districts that contribute most to the malaria burden and is deploying tailored interventions.

Ghana: Implemented four strata based on the malaria burden and is deploying tailored interventions by strata; the country is also deploying chemoprevention in low-transmission areas to support elimination activities.

Mauritania: Carried out stratification to identify health districts suitable for the implementation of malaria elimination interventions.

Senegal: Uses stratification to efficiently deploy malaria interventions to maximise the impact of limited resources.

Tanzania: Uses its national malaria scorecard to monitor the implementation of tailored packages of interventions.

Strengthening Data Quality and Availability

The adoption of digital tools facilitate more real-time reporting and integration of novel data sources enables Member States to proactively track and confront the threats posed by the perfect storm. The availability and use of additional data such as climate and geospatial data and technologies such as artificial intelligence help strengthen planning and implementation of malaria interventions. For example, integrating climate data into digital health platforms (e.g., DHIS2, malaria data repositories and scorecard management tools) enables countries to better forecast commodity needs and respond in the real-time to adverse climate events that cause malaria upsurges. These new sources of data can also be integrated directly into national malaria scorecards to drive accountability and action.

The increased availability of mobile and other internet-enabled technologies presents new opportunities to build local capacity for capturing, interpreting, and using data. Local data entry improves data quality and real-time availability, enabling quicker and more effective responses to malaria upsurges. Likewise, regular data reviews at a local level support community owned and led responses.

Rwanda, Togo, and Uganda are integrating climate data into their national health information systems. Mozambique, Malawi, Ethiopia and Tanzania are piloting the use of climate data.

Burkina Faso: Launched a malaria data repository that integrates all the elements of malaria control on the same platform (e.g., epidemiological, data quality, stock management, climate, entomological, weekly human resources, finances, interventions, vaccinations).

Cameroon: Implemented a monthly reporting mechanism to directly capture data from more than 9,000 community health centres.

Kenya: Integrating entomological data into DHIS2 to support the deployment of vector control interventions and respond to upsurges; completed the end-to-end digitalisation of the mass net campaign; enabled 103,000 Community Health Promoters to report vital health information for malaria and NTDs.

Malawi: Integrated community health information into DHIS2 to enhance planning and visibility into net distribution; used data to identify a decline in the efficacy of the first-line malaria treatment resulting in the planned introduction of a new treatment in 2025.

Senegal: Integrating genomic data into its health information management system to enhance vector and disease surveillance.

Uganda: Enabled daily reporting for community health services.

Zambia: Enhanced the data collected in DHIS2 to report on where and how nets were being distributed during the 2023-2024 universal LLIN campaign, increasing transparency and accountability.

Scorecard Management Tools

The continent-wide adoption of scorecard tools underscores a shared commitment to transparency, accountability, and action. As RECs and Member States continue to develop and strengthen these tools, they are empowering citizens, government officials, and health professionals alike to participate actively in building stronger, more resilient health systems.

ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action

The ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action continues to be an important tool for mobilising political will. This quarterly scorecard reports on key indicators across all Member States related to malaria, maternal and child health, and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). The scorecard, along with quarterly narrative reports, is distributed to Heads of State and Government, AU Ambassadors, and Ministers of Health, Finance and Foreign Affairs.

New indicators introduced in 2024

- Inclusion of vector-borne diseases in Nationally Determined Contributions

- Roll out of next-generation nets and insecticides

- Achievement of WHO targets for mass drug administration for NTDs

- Countries with NTD Budget lines

Regional Scorecard Tools

Each of the RECs has developed a regional strategy and implemented a scorecard tool for driving accountability and action. Progress against these is reviewed in meetings of Heads of State and Government and Ministers.

National & Subnational Scorecard tools

44 Member States use scorecard tools to drive accountability and action at all levels of the health system. The expansion and decentralisation of scorecard tools empower Member States to track health performance, allocate resources based on real-time data, and hold stakeholders accountable for improving health outcomes. Scorecards help transform health data into action, making it accessible to everyone. Ministries of Heath, End Malaria Councils, youth, parliamentarians, and civil society are key users of national and subnational scorecards. By providing concrete data on malaria prevalence and prevention efforts in communities, multisectoral stakeholders can advocate for changes in policies and public expenditures, drive action and mobilise financial and in-kind resources. They can use the data to organise and empower communities (e.g., to reduce of mosquito breeding sites), conduct awareness campaigns on the importance of using insecticide-treated nets, and engage with local leaders on the need for consistent access to malaria treatment and preventive measures.

Scorecard tools also offer new opportunities to look beyond health sectors and integrate data from related areas like agriculture and environmental management. and integrating data from these sectors into scorecards can lead to more effective malaria strategies. By ensuring that ministries across agriculture, environment, gender, information, energy, mining, and health are aligned in responding to these challenges, countries can foster a more integrated and efficient response to disease outbreaks and health threats. Country scorecards can also support advocacy, action, and accountability on issues related to gender, including barriers to accessing health facilities and services.

Ethiopia, Gambia, Niger & Zambia: Trained members of Parliament to use scorecards, promoting data literacy and enabling them to use health data in their advocacy and resource allocation efforts.

Ghana: Trained journalists and focused on an integrated strategy for reviewing scorecards and creating joint action plans. This has increased public engagement and fostered accountability as media professionals use scorecards to track and report on health performance.

Nigeria: Made substantial progress in decentralising scorecards down to the Local Government Area level in multiple states, facilitating more localised tracking and decision-making.

Zanzibar: Empowered community members to monitor local health services and actively participate in improving service delivery via the community scorecard approach.

7. Build Collaborative Partnerships for Research, Innovation and Local Manufacturing

Member States are encouraged to pursue innovative strategies and locally manufacture malaria commodities.

Member States have a large number of existing research institutions, universities, and companies that can test, trial, and support the rolling out of malaria interventions. Moreover, regional institutions like the African Medicines Agency can help create an environment conducive for the deployment of new commodities and innovations.

Research and Innovation

The African Union has issued a decision calling on Member States to 1-3% of national budgets towards research. These resources provide an opportunity to increase domestic investment via national universities and research institutions (e.g., molecular and genomic research, diagnostic tools, medicines, vector control).

African Medical Agency

In 2024, the African Medicines Agency (AMA) has continued to make significant progress toward its goal of harmonising and strengthening the regulation of medicines and medical products across Africa. As the second specialised health agency of the African Union, AMA aims to improve access to safe, effective, and high-quality medicines by supporting local pharmaceutical production, coordinating joint assessments of medicines, and promoting information sharing among national and regional regulatory authorities.

With 27 countries having ratified the AMA Treaty by 2024, AMA is on track to streamline regulatory processes across the continent, reducing the burden of substandard and falsified medicines. Rwanda has been selected as the headquarters, and the agency is now operationalising its leadership structure, with support from the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which has committed €10 million for scientific and regulatory training. This collaboration will enable AMA to supervise medicines effectively and advance the use of digital tools to improve regulatory transparency and efficiency.

Local Manufacturing

Both the Catalytic Framework and the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa underscore the importance of local manufacturing. Tremendous progress is being made by the malaria community with enhanced focus on technology transfer and manufacturing of malaria commodities in Africa (next-generation nets, medicines, and vaccines). Locally manufacturing malaria commodities would support economic growth, promote the long-term availability and prioritisation of malaria commodities, and mitigate some of the effects of supply chain disruptions (e.g., as seen during the COVID-19 Pandemic).

ALMA continues to collaborate with development banks and organisations to promote local manufacturing. AfDB, African Pharmaceutical Technology Foundation (APTF) and ALMA have agreed to establish an antimalarial manufacturing programme as a next step for AfDB and the APTF’s investment in local manufacturing opportunities for malaria commodities. ALMA also supported AUDA-NEPAD and AUC in hosting the conference on Vector Control Products Registration and Regulation. Recommendations will be presented in a policy brief.

Several Member States are pursuing initiatives to locally produce malaria commodities, including medicines, insecticides, and nets. However, significant effort is needed to accelerate technology transfer to capable manufacturers, to secure WHO approval, and build sustainable supply chains for sourcing raw ingredients and for distribution.

Burkina Faso: The pharmaceutical manufacturing plant ‘Propharm’ has initiated the process leading to local production of antimalarial drugs.

Nigeria: Swiss Pharma Nigeria Ltd, with support from MMV and Unitaid, became the first Nigerian manufacturer of WHO-prequalified sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine. The Unlocking the Healthcare Value Chain resulted in the signing of an MoU with Vestergaard, which is a major step towards establishing the country as the first African manufacturer for Dual AI Nets.

8. Coordinate and Collaborate across Borders

Member States and the Regional Economic Communities are encouraged to facilitate cross-border data sharing, surveillance, coordination, and financing.

Malaria knows no boundaries and addressing many of the threats of the Perfect Storm will require cross-border collaboration and coordination. Humanitarian emergencies and increased regional trade will require addressing the cross-border movement of people. Mitigating insecticide resistance will require effective cross-border surveillance and coordination of vector control and case management interventions (including subnational tailoring).

Regional Economic Communities

As the African Union has devolved responsibilities, the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) have taken a more proactive role in addressing malaria elimination. Each has developed a strategic plan and scorecard to support accountability and action at the regional level.

The RECs are actively working on implementing cross-border initiatives to harmonise strategic priorities, facilitate data sharing, and address challenges like drug resistance and climate change

EAC: The East African Community’s Great Lakes Malaria Initiative hosted the first regional conference on antimalarial drug resistance to develop a detailed action plan to align priorities at the regional and national level for monitoring and addressing resistance.

ECCAS: Implementing a regional strategy focused on strengthening cross-border collaboration, enhancing surveillance systems, and promoting the use of effective vector control measures.

ECOWAS: The Sahel Malaria Elimination Initiative hosted a meeting to review progress in the workplan and to discuss opportunities to strengthen regional and national resource mobilisation.

IGAD: The IGAD Climate Adaptation Strategy prioritises scaling up of malaria interventions, including for displaced populations.

SADC: Produces an annual report highlighting activities, progress, and priorities for malaria control across the region. This report is produced in consultation with experts from Member States and development partners. The report is then submitted to the Heads of State and Government during the REC’s annual summit.

Recommended Actions

Member States and their partners need to make a big push to get the continent on track to eliminate malaria. This will require strong political will, decisive action by leaders across all sectors, a commitment of domestic resources and integrated resource mobilisation, accelerated deployment of new interventions, and health systems strengthening.

Strengthen Political Will & Leadership

- Translate commitments into action by integrating the priorities of the Catalytic Framework, mid-term review roadmap, into the national development agenda, strategic and action plans, and policies.

- Recruit malaria focal points across all line ministries to proactively identify how each sector can contribute to malaria elimination, allocate funding, and implement policies that create an enabling environment for malaria elimination.

- Launch a whole-of-society and whole-of government campaign to end malaria (e.g., Zero Malaria Starts with Me!).

Mobilise Sufficient & Sustainable Resources

- Allocate increased national funding to support malaria interventions, including as a pathfinder for health integration, including in pandemic preparedness and response, and climate resilience and financing.

- Support the replenishment of key financing mechanisms, including The Global Fund and GAVI.

- Integrate malaria into development-bank financed initiatives.

- Launch national End Malaria Councils & Funds to facilitate resource mobilisation from new donors and the private sector.

Enhance Multisectoral Coordination & Action

- Convene youth leaders to participate in decision-making processes, mobilise communities, and promote malaria interventions.

- Train and empower religious, traditional and other community leaders to champion malaria, disseminate social and behavioural change communications, and drive community-level dialogues.

- Coordinate multisectoral activities through a national End Malaria Council.

Strengthen National Health Systems & Adopt the Latest Guidance

- Further integrate malaria into other health services such as integrated community case management, vaccination, and antenatal care.

- Scale up the evidence-based and targeted deployment of next-generation malaria commodities and novel interventions.

- Conduct risk mapping for upsurges and climate emergencies and develop risk mitigation strategies and plans.

Use Strategic Information for Action

- Implement the ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action and associate quarterly reports and recommended actions as an accountability mechanism for tracking and driving progress on the acceleration agenda.

- Integrate climate data and other multisectoral data into national health information systems to support responsive and resilient health systems in evolving climates and environments.

- Build national capacity for scorecard tools to support subnational stratification and tailoring, decentralisation, and monitoring of actions, as well as expanding the use of scorecards beyond the health sector.

- Develop multisectoral scorecards to ensure data is systematically used to identify opportunities for collaboration across sectors (e.g., agriculture, finance, environment).

Build Collaborative Partnerships for Research, Innovation & Local Manufacturing

- Invest in developing research and manufacturing capabilities to encourage and scale up innovations, including novel interventions and medicines, diagnostics, and surveillance tools.

- Harness academia and research institutes to drive malaria research and support the development of evidence-based interventions and policies, including those that reduce costs, drive efficiencies, and promote social and economic development.

- Support regional initiatives, such as the AMA Treaty, and work with RECs to accelerate market access for new interventions and market shaping.

- Support pre-qualification, regulatory approval, and market-shaping for locally produced commodities.

Coordinate and Collaborate Across Borders

- Develop mechanisms for sharing data across borders, including real-time information related to upsurges, resistance, and other challenges.

- Strengthen data-sharing, planning, surveillance, resource mobilisation, and other cross-border activities via RECs.

Annex: 2024 Neglected Tropical Diseases Progress Update

Status of NTD elimination in Africa

In June 2024, WHO validated Chad as the 7th country to eliminate the gambiense form of human African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness, as a public health problem. Additional countries (e.g., Burundi, Niger and Senegal) submitted or are working on elimination dossier for NTDs.

Digitalisation

ALMA Scorecard for Accountability & Action

In 2024, ALMA held four consultative meetings to discuss with key partners including Uniting to Combat NTDs, the African Union Commission, WHO (AFRO, Headquarters, and the Expanded Special Project for Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases (ESPEN)), Kikundi, and NTD Managers on possible additional indicators to be added in the ALMA scorecard to support monitoring the implementation of the Continental Framework for NTDs. A meeting was held with WHO to discuss the possibility of increasing the red threshold of NTD coverage index from 25 to 50 and to discuss possible indicators to be added on the ALMA scorecard. WHO/HQ committed to review the threshold levels in 2025.

ALMA included an indicator on whether Vector Borne Diseases are included in Nationally Determined Contributions to address climate change. This indicator will support advocacy for prioritisation of Vector Borne diseases in NDCs and costed plans at country level, including in support of additional resource mobilisation.

National NTDs Scorecards

Twenty-two Member States have developed national NTDs scorecards, including South Sudan, Cameroon and Ghana which launched in 2024. These scorecards have enhanced the profile of NTDs at the national level and improved NTD data reporting. Angola, Burundi, Burkina Faso, Congo, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Malawi, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Zambia increased the number of NTD indicators in national Health Management Information Systems (e.g., DHIS2) and now over 75% of NTD Master Plans are reported into DHIS2. Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana, Senegal and Rwanda linked their NTD scorecard with DHIS2. Burkina Faso, Burundi, Congo, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Malawi, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania and Zambia also increased domestic resources for NTDs and mobilised more resources from partners to improve gaps identified during the scorecard analysis.

Angola: A review of the scorecard revealed no coverage of MDA in 12 provinces. This led to resource mobilisation from the END Fund.

Burkina Faso: Identified a low leprosy cure rate on its scorecard, resulting in a recommendation to intensify leprosy control measures. The country improved from 67% in 2023 to 81% in 2024 after conducting community sensitisation and health care providers training on leprosy case management.

Kenya: Scorecard analysis led to the mapping of snake bite cases in order to put in place prevention and control measures. Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL) treatment centres reported increased coverage from 81% in 2022 to 100% in 2024.

Niger: Members of Parliament were trained on the scorecard, which resulted in NTDs being included in the national health budget ($524,000 in 2024).

Tanzania: The scorecard increased awareness with Members of Parliament and other political leaders. This increased prioritisation of NTDs with 15 councils increased the budget allocated to NTDs in 2024 and the total government spending increasing to ($6.9 million).

During 2024, 11 Member States shared their NTDs scorecards publicly, 29 countries reported having budget line for NTDs and 584 training certificates were issued to various stakeholders relating to the use of NTD scorecards.

Multisectoral Advocacy, Action & Resource Mobilisation

A survey was conducted during 2024 to assess the degree of domestic funding for NTDs in national budgets. Twenty-eight Member States responded to the survey. Of those who responded, 64% have budget lines for NTDs (including partner fundings) and 36% allocate government funding.

Glossary

ALMA

African Leaders Malaria Alliance

AMA

African Medical Agency

ANC

Antenatal Care

AYAC

ALMA Youth Advisory Council

CHW

Community Health Worker

EMC / EMF

End Malaria Council or End Malaria Fund

EPI

Expanded Programme on Immunisation

HBHI

High Burden to High Impact

iCCM

Integrated Community Case Management

IDA

World Bank International Development Association

IPTp

Intermittent Preventative Treatment of Pregnant Women

IRS

Indoor Residual Spraying

ITN

Insecticide-treated Net

NTDs

Neglected Tropical Diseases

RDT

Rapid Diagnostic Test

REC

Regional Economic Community

SMC

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention

Acknowledgements

This report has been prepared by the African Union Commission, African Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA), and the RBM Partnership to End Malaria. The drafting and revision of this report included contributions from national malaria control programmes, development partners, and other stakeholders from across the continent and the global community.

- Sheila Tamara Shawa-Musonda (AUC)

- Whitney Mwangi (AUC)

- Eric Junior Wagobera (AUC)

- Itete Karagire (EAC)

- Ahmed Hassan Ahmed (IGAD)

- Sidzabda Christian Bernard Kompaore (Burkina Faso)

- Marcellin Joel Ateba (Cameroon)

- Hassane Ali Outhan (Chad)

- Gudissa Assefa (Ethiopia)

- Duarte Falcão (Guinea-Bissau)

- Kibor Keitany (Kenya)

- Andrew Wamari (Kenya)

- Godwin Mwakanma Ntadom (Nigeria)

- John H. Sande (Malawi)

- Issac Adomako (Malawi)

- Mohamed Ainina (Mauritania)

- Sene Doudou (Senegal)

- Joseph Panyuan Puok (South Sudan)

- Nakembetwa Marco (Tanzania)

- Mathias Mulyazaawo (Uganda)

- Maulid Issa Kassim (Zanzibar)

- James Dan Otieno (WHO Kenya)

- Philippe Edouard Juste Batienon (RBM Partnership)

- Yacine Djibo (Speak Up Africa)

- Melanie Renshaw (ALMA)

- Samson Katikiti (ALMA)

- Abraham Mnzava (ALMA)

- Tawanda Chisango (ALMA)

- Stephen Rooke (ALMA)

- Hilaire Zon (ALMA)

- Aloyce Urassa (ALMA Youth Advisory Council)

- John Mwangi (Kenya Malaria Youth Corps)

Endnotes

- WHO, World Malaria Report 2024. ↩︎

- WHO, Countries and Territories Certified Malaria-Free, https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/elimination/countries-and-territories-certified-malaria-free-by-who. ↩︎

- African Union, Catalytic Framework to End AIDS, TB and Eliminate Malaria in Africa by 2030, https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/32904-file-catalytic_framework_8pp_en_hires.pdf. ↩︎

- WHO, World Malaria Report 2024. ↩︎

- ALMA, Preliminary Analysis of Country Funding Requests to The Global Fund (2024). ↩︎

- Malaria Atlas Project, New Malaria Data Warns Millions at Risk (Sept. 2024), https://malariaatlas.org/news/new-malaria-data-warns-millions-at-risk/. ↩︎

- The RBM Partnership to End Malaria, Malaria to Kill 300,000 More People if Critical Funding is Not Received (Sept. 2024), https://www.endmalaria.org/news/malaria-kill-300000-more-people-if-critical-funding-not-received. ↩︎

- The Global Fund, New Nets Prevent 13 Million Malaria Cases in Sub-Saharan Africa (Apr. 2024), https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/news/2024/2024-04-17-new-nets-prevent-13-million-malaria-cases-sub-saharan-africa/. ↩︎

- Djibouti (2012), Ethiopia (2016), Sudan (2016), Somalia (2019), Nigeria (2020), Eritrea (2022), Ghana (2022), Kenya (2022). WHO, Surveillance and Control of Anopheles Stephensi: Country Experiences (2024), https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/378091/9789240094420-eng.pdf. ↩︎

- Dr. Marina Romanello et al., The 2022 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Health at the Mercy of Fossil Fuels (Oct. 2022). ↩︎

- Sadie J. Ryan et al., Shifting Transmission Risk for Malaria in Africa with Climate Change: A Framework for Planning and Intervention, Malaria J. (May 2020). ↩︎

- Boston Consulting Group, Preliminary Analysis: Climate & Malaria (Sept. 2024). ↩︎

- Sadie J. Ryan et al., Shifting Transmission Risk for Malaria in Africa with Climate Change: A Framework for Planning and Intervention, Malaria J. (May 2020). ↩︎

- Oxford Economics & Malaria No More UK, The Malaria ‘Dividend’: Why Investing in Malaria Creates Returns for All (May 2024). ↩︎

- The Global Fund, Malaria (last updated Sept. 2024), https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/malaria/. ↩︎

- WHO, New and Updated WHO Malaria Guidance (last accessed Nov. 2024), https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/guideline-development-process/new-and-updated-malaria-guidance. ↩︎

- WHO, Malaria Vaccine: Who Position Paper (May 2024), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer-9919-225-248. ↩︎

- GAVI, Routine Malaria Vaccinations (July 2024), https://www.gavi.org/news-resources/media-room/communication-toolkits/routine-malaria-vaccinations. ↩︎