Foreword

We face a growing number of threats to achieving our goal of eliminating malaria in Africa by 2030. Despite political will and knowing how to defeat malaria, we lack the resources necessary to fully implement our national malaria strategic plans, sustain essential life-saving malaria services, and deploy new and more effective interventions to address increasing biological threats. Together with the global community, we the leaders of Africa need to act now to drive accountability, action, advocacy, and resource mobilisation to end this disease once and for all.

Member States are particularly impacted by the global financial crisis and will be unable to sustain existing levels of essential malaria interventions—especially in 2026. We face at least a $1.5 billion USD budget gap just to sustain basic malaria services, especially for vector control. Countless experiences across Africa tell us that malaria comes roaring back when funding stops and interventions cease. We foresee significant upsurges in cases and deaths—particularly amongst vulnerable populations like pregnant women and children—unless urgent action is taken. An additional $5.2 billion USD is needed annually to make progress towards elimination and another $11 billion USD annually to support climate adaptation in the Health Sector.

We are concerned about the declining efficacy of existing, lower-cost interventions (e.g., insecticides, anti-malarial medications, and rapid diagnostic tests). We have highly impactful and effective next-generation commodities, but they cost more and therefore exacerbate our resource challenges. Further market-shaping is needed to bring down costs and capture economies of scale.

Climate change presents a major threat to health and the fight against malaria. Warmer temperatures and increased precipitation will lead to increased malaria transmission. More frequent and more powerful natural disasters will destroy infrastructure and displace populations. In 2023, Cyclone Freddy impacted Southern Africa not once, but twice and for an unprecedented length of time. Hundreds of health facilities were damaged or destroyed, populations were left unprotected against mosquitoes, and restoring services was hindered by washed out roads and infrastructure. Without urgent action, malaria cases and deaths, as well as neglected tropical diseases, will become the face of climate change and health.

As we first indicated in last year’s report, we remain concerned about the Anopheles stephensi mosquito. This mosquito is more likely to transmit malaria in urban areas, our fastest growing population and economic centres.

An integrated agenda is needed to address these growing threats. Malaria must be prioritised as a pathfinder for health systems strengthening and pandemic preparedness. Malaria intervention adaptation must also be prioritised within the climate change and health agenda. National End Malaria and NTD Councils and Funds are needed to sustain malaria high on national development and financing agendas and engage the domestic private sector. Member States should also prioritise health and malaria in World Bank International Development Association (IDA) funding and advocate for the creation of a new Malaria Booster Programme to close immediate gaps. We also call on existing partners and donors to increase current funding for malaria.

H.E. Moussa Faki Mahamat

Chair, African Union Commission

H.E. Umaro Sissoco Embaló

President, Guinea-Bissau

Chair, ALMA

Dr. Michael Adekunle Charles

CEO, RBM Partnership to End Malaria

Malaria Progress & Challenges

Progress towards 2030 targets

According to the WHO, there were an estimated 236 million malaria cases (95% of global cases) and 590,935 malaria deaths (97% of global deaths) in African Member States in 2022.1 As was the case in last year’s report, just four Member States account for nearly half of global malaria cases: Nigeria (27%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12%), Uganda (5%), and Mozambique (4%).

Across the continent, 1.27 billion individuals are at risk of malaria infection. Amongst this population, there were 186 cases per 1,000 persons and 47 deaths per 100,000 persons. Compared to 2000, this represents a 38% reduction in malaria incidence and 60% reduction in malaria mortality. Over the past two decades, 1.6 billion malaria cases and 10.6 million malaria deaths have been avoided in Africa.

Progress remains stalled, and the continent is not on track to achieve its goal of controlling and eliminating malaria by 2030.2 Since 2015, malaria incidence has declined by 7.6% and mortality by 11.3%, well short of African Union’s interim goals of 40% reductions by 2020 and 70% by 2025. Of the 46 Member States reporting incidence of malaria, seven have achieved a 40% reduction in either malaria incidence or mortality.3 Significant gains will need to be made to get the continent back on track.

Cabo Verde Successfully Eliminates Malaria

After reporting zero indigenous cases for four consecutive years and zero deaths since 2018, WHO certified that Cabo Verde successfully eliminated malaria.

An Expanding Toolkit

A number of new and next-generation commodities have been added to the malaria toolkit, increasing the tools available to countries to combat malaria.

We have the tools to drive down malaria, a package of interventions that includes vector control, preventive medicines, testing, and treatment. These are joined by a safe and effective malaria vaccine, which could save the lives of tens of thousands children every year. With sustained investment and scaled-up efforts to reach those most at risk, malaria elimination in many countries is in reach.

Dr. Tedros Ghebreyesus, Director-General of WHO (World Malaria Day 2023)

Vector Control Commodities: In 2023, WHO approved the preferential use of Pyrethroid-chlorfenapyr nets. These dual-active ingredient nets are 43% more effective compared to pyrethroid-only nets4 and remained 40% more effective at the end of three years.5 This year, Member States significantly expanded the use of PBO nets and Pyrethroid-chlorfenapyr nets. Continued scaling-up of these commodities is essential to protecting vulnerable populations.

Antimalarial Medications: Inlate 2022, WHO approved Artesunate-pyronaridine for treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Countries are in the process of procuring and deploying it out to complement existing ACTs.

Malaria Vaccines: In October 2023, WHO recommended the second vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, for the prevention of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children.6 Both the R21 and previously approved RTS,S vaccines are safe and efficacious in preventing malaria in children. There is no evidence to date showing that one performs better than the other.7 The two vaccines expand the malaria toolkit and should be deployed alongside existing interventions. Resources remain insufficient to implement all interventions and the choice of whether to deploy a vaccine and which one should be based on product characteristics, programmatic needs, supply availability, the likelihood of being able to scale up, and long-term affordability, particularly for countries approaching Gavi transition. To date, Gavi has approved support for deploying the RTS,S vaccine in 18 of the 28 Member States that requested assistance.

Example: Malawi Rollout of RTS,S Vaccine (2023)

Malawi rolled out the RTS,S vaccine during 2023. In March, the Minister of Health promoted adoption of the vaccine and encourages communities in targeted districts to take it up. Through September, RTS,S had been distributed in 11 districts (out of the 28) with 661,714 children under the age of 5 having received at least one dose. Community Health Workers referred to as Health Surveillance Assistants are in the forefront of delivering the vaccine to the community.

Africa faces growing threats that increase the risk of cases and deaths

Africa is at the centre of a perfect storm that threatens to disrupt essential life-saving malaria services and undo decades of progress. Member States and the global community need to act urgently to mitigate the adverse effects of the ongoing financial crisis, increasing biological threats, climate change, and humanitarian crises. These threats represent the most serious emergency facing malaria in 20 years and will lead to malaria upsurges and epidemics if not addressed.

Significant Financial Gaps

African countries face significant budget gaps that require urgent resource mobilisation. An analysis by The Global Fund identified that Member States require at least $1.5 billion USD just to sustain existing levels of malaria interventions between 2024-2026.8 These gaps are linked to the ongoing global financial crisis with increased costs of delivering commodities and essential interventions to communities. The need for higher-cost, next-generation commodities to address widespread insecticide and increasing partial drug resistance9 adds further pressure on constrained budgets. History demonstrates that disruptions to malaria-related services result in almost immediate upsurges with cases returning to pre-control levels. The anticipated shortfalls in 2026 could have a similar outcome to the worst-case scenarios estimated at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic: malaria deaths at risk of doubling.10 Another $5.2 billion is needed annually for the continent to make progress towards elimination.11

Malaria is a disease of poverty disproportionately concentrated in low-income countries and vulnerable populations. African countries are the most affected by the ongoing financial crisis, face high levels of debt and default risks, and have limited domestic resources because of low tax revenues and high borrowing costs.12 Despite the difficult financial situation, some Member States have increased domestic funding for health and malaria (e.g., the Republic of Zambia increased funding for health by 174% and malaria commodities by 222% between 2021 and 2023, the Republic of Benin increased funding for health by 140%). In 2022, domestic funding for malaria increased by $300 million USD amongst Member States. However, Member States continue to rely on donor funding with 70% of malaria resources coming from external funders.13

An Urgent Call to Action (2023)

High-level advocacy events were held with Heads of State and Government, Ministers of Health and Finance, and AU and UN ambassadors throughout 2023 to advocate for increased malaria funding. At the UNGA side meeting on malaria financing, H.E. President Umaro Sissoco Embaló called for Member States to close gaps and fully finance national malaria strategic plans by:

- Launching multisectoral, high-level National End Malaria and NTD Councils and Funds to maintain malaria and NTDs high on the national development and resource mobilisation agenda, to increase public and private sector domestic funding.

- Prioritising health and malaria financing in country allocations of World Bank International Development Association (IDA) funding.

- Advocating for The World Bank to commit to a new Malaria Booster Programme to facilitate additional financing needed to close immediate gaps, with additional commitments from regional development banks.

- Sustaining advocacy for increased international financing from new and traditional donors.

- Promoting integrated approaches with malaria as a pathfinder for health systems strengthening, pandemic preparedness, climate change and health mitigation and adaptation.

Climate Change Threat to Health

The science is clear: Africa will be the biggest casualty of climate change unless urgent action is taken now.14 Africans are disproportionately exposed to the risks of climate change (e.g., 55-62% of the African labour force works in climate-dependent agriculture). Low-income families, women and children face the greatest risks.15 In 2022, 110 million people on the continent were affected (60% of the global total)16, 17 despite contributing only 10% of global carbon emissions. Member States were amongst the hardest hit in 2023.18

Climate change threatens efforts to ending malaria and build resilient and sustainable health systems. A warmer and wetter climate accelerates the development of parasites and mosquitoes. Even areas with a low burden will be affected. The number of months suitable for malaria transmission in African highlands has increased by 14%19 and an estimated 147-171 million additional people will be at risk of malaria in Africa by the 2030s.20

Climate-fuelled disasters displace millions and destroy roads and health facilities, reducing the accessibility of health services. Frequent disasters undermine Member States’ ability to recover and the financial feasibility of doing so.

Example: Cyclone Freddy (2023)

Cyclone Freddy impacted Madagascar, Mozambique, Malawi, and other Southern African countries in 2023. Freddy was the longest-lasting cyclone in recorded history, leading to widespread flooding. 233 health facilities were damaged or destroyed and hundreds of thousands of people were displaced—disrupting health services, IRS, ITN distribution, and surveillance. The response was supported by multisectoral stakeholders. In Malawi, the Department of Disaster Management Affairs led coordination efforts. The Global Fund’s Emergency Fund provided a $1 million USD grant to Mozambique enabling the NMCP to respond quickly in worst hit areas. Cyclone Freddy was only the latest of many cyclones that have impacted this region.

The health sector faces an urgent need to reduce carbon emissions and combat the effects of climate change by:

- Decarbonising: Reduce supply chains’ carbon footprint, locally manufacture commodities, use renewable energy sources

- Collaborating across sectors: Implement integrated solutions (e.g., improving irrigation can prevent mosquito breeding sites)

- Adapting: Build capacity to plan for climate risks, recruit additional health workers, integrate climate data into health information systems, and strengthen service delivery by deploying the full malaria toolkit, accounting for social determinants of health, and improving emergency preparedness

- Financing: Align country and donors climate funding priorities to close the $11 billion USD annual funding gap for health system adaptation.

Insecticide Resistance

Thirty-five Member States have confirmed resistance to three or four classes of the insecticides used to combat malaria.21 Insecticide resistance reduces the efficacy of the primary vector control interventions, ITNs and IRS. Next-generation vector control commodities are significantly more effective and will have greater impact—albeit at a higher cost. Market-shaping efforts by Member States and partners have the potential to mitigate some of the costs, as evidenced by recent price reductions in dual ai nets.

Drug Resistance

Member States and global partners continue to raise concerns about resistance to antimalarial drugs, including partial resistance to artemisinins, the central component in all artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT) used to treat uncomplicated P. falciparum. Resistance delays the clearing of malaria parasites from patients and reduces treatment efficacy. WHO launched a global Strategy to Respond to Antimalarial Drug Resistance in Africa22 proposing that countries should: (1) improve detection of drug resistance, (2) delay the emergence of resistance, and (3) contain the spread of resistant parasites. Member States are developing and implementing national strategies monitoring for drug resistance and ensuring proper testing and treatment in accordance with national and global guidelines. All countries in Africa are increasing monitoring and surveillance, with those countries that have detected partial resistance working to introduce new treatment regimens.

Reduced Detection by Rapid Diagnostic Tests

Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) have significantly expanded the capacity of health workers to diagnose malaria, especially at the community level. However, genetic mutations in the malaria parasite have resulted in the loss of antigens targeted by specific RDTs. This increases the risk that malaria cases are missed. To address this, Member States are implementing surveillance systems to detect parasite with these mutations and deploying other RDTs that target alternative antigens.

Anopheles stephensi

The invasive An. stephensi mosquito has been detected in eight Member States (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Sudan, Somalia). Unlike other malaria vectors in Africa, An. stephensi mosquitoes thrive in urban areas, where they breed in manmade water containers, increasing the risk of urban malaria. Anopheles stephensi‘sbiting behaviour suggests that indoor vector control methods (e.g., ITNs) may not be as effective and it is resistant to many of the insecticides commonly used.23 In 2023, WHO updated its Initiative to Stop the Spread of Anopheles stephensi in Africa.24 Core priorities are to increase collaboration, strengthen entomological surveillance, improve information exchange, develop guidance and prioritise research. Countries have increased their surveillance efforts and where detected are working to control An. stephensi.

Human Capacity Constraints

Member States face significant human resources constraints that limit their capacity to scale up malaria-related interventions and surveillance. National Malaria Programmes report gaps in management and operational capacity. Shortages of laboratory technicians limit the availability, accessibility, and timeliness of slide microscopy to confirm malaria cases. Limited entomologists undermine active monitoring and early detection of insecticide resistance and new vectors. Programmes also often lack staff dedicated to supporting multisectoral and cross-border initiatives. There is also a shortage of researchers. There is also a need to recruit and train community health workers (CHWs). CHWs extend malaria and other health services (e.g., social and behavioural change communications and case management) at the community level. CHWs are particularly important for diagnosis and treatment of malaria in hard-to-reach areas and in strengthening pandemic preparedness and response.

Humanitarian Crises

Between 2019-2022, 41 malaria endemic countries experienced humanitarian crises, resulting in internally displaced populations, refugees, and unsafe environments. An estimated 169 million Africans were affected across 15 Member States in 2022.25 Sustaining malaria-related interventions during humanitarian crises is essential to preventing upsurges in cases and deaths. National malaria programmes report concerns about reduced access to health services and disruptions to vector control and prevention campaigns. Health should be integrated into the broader humanitarian response26 and Member States are encouraged to ensure that the national malaria programmes have access to affected populations and work with NGOs, international emergency organisations, and other partners to implement interventions and provide a mechanism for receiving funding and procuring and distributing commodities.

Expanding the “High Burden to High Impact” approach can help Member States address these challenges

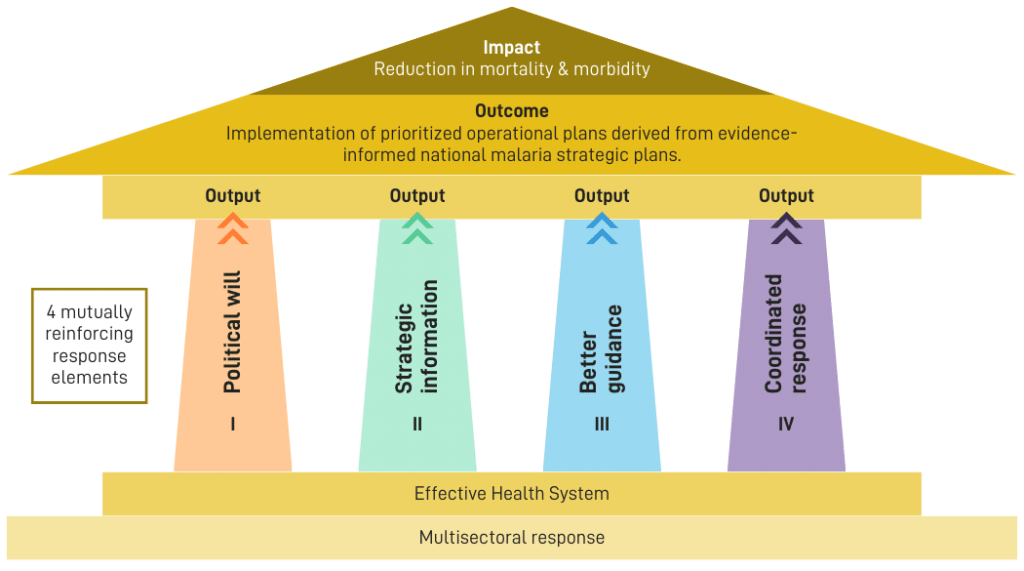

The High Burden to High Impact (HBHI) approach was launched in 2018 by WHO and the RBM Partnership to End Malaria with a focus on the 10 highest-burden countries in Africa. HBHI seeks to accelerate progress against malaria by improving planning and execution of the public health response across four areas: political will, strategic information, better guidance, and a coordinated response. HBHI also recognizes the foundational supporting role played by the overall health system and the multisectoral response.

A recent evaluation of the approach highlighted key successes including:

- The use of subnational stratification and tailoring in all HBHI countries to identify and prioritise the most impactful intervention packages, which was reflected in Member State’s Global Fund funding requests.

- The use of real-time data and scorecard accountability and action tools enable countries to more effectively address bottlenecks and drive action.

- The launch of End Malaria Councils and Funds in four HBHI countries (Uganda, Mozambique, Nigeria and Tanzania) helped maintain malaria high on the national development and financing agenda and encourage multisectoral advocacy, action, and resource mobilisation.

Digitalisation

Data Repositories and Health Management Information Systems

Digitalisation of health data continues to improve across Africa. Access to real-time data is essential to monitoring and evaluating the implementation and efficacy of interventions and early detection of upsurges. Data also enables Member States to drive accountability, make evidence-based decisions on the deployment and subnational tailoring of interventions, and budgeting. Countries, especially the High Burden High Impact countries are increasingly using sub-national stratification and tailoring to support better targeting of malaria interventions for maximum impact. Subnational tailoring of malaria interventions is the use of local data and contextual information to determine the most appropriate mixes of interventions and strategies, for a given area, for optimum impact on transmission and burden of disease.

Health Management Information Systems continue to improve as computer technologies and connectivity expand. The most prominent tool used by 52 Member States is the District Health Information System (DHIS2). DHIS2 supports digitalisation of health information at all levels (i.e., national down to health facility), reporting of performance against key indicators, and integration with a number of analytics and data visualisation platforms (e.g., ALMA Scorecard Management Tools Web Platform).

Additionally, nine Member States (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Guinea, Mozambique, Nigeria, Uganda, Tanzania, and Sudan) have implemented national malaria data repositories with support from WHO. These national databases collect data in near real-time from health facilities. This has led to improvements in the quality of malaria data for operational planning and budgeting, accountability, and action.

Scorecard Management Tools

Scorecard management tools provide a mechanism for translating data into accountability and action. The scorecards summarise performance across key performance indicators tied to continental, regional, and national strategies. The presentation of the information in a simple and accessible format enables scorecards to be easily integrated and institutionalised into existing governance processes across sectors.

ALMA Scorecard for Accountability & Action

The ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action is a continental scorecard summarising national performance on priority indicators for malaria and key health areas including Neglected Tropical Diseases and maternal and child health requested by the African Heads of State and Government. The scorecard is produced quarterly and distributed to all Heads of State and Government, Ministers of Health and Finance, AU Ambassadors, and other stakeholders. The scorecard is published online. Each country also receives a country report which tracks progress and identifies and tracks progress against recommended actions to address areas of underperformance, as well as a quarterly overview report from ALMA’s Executive Secretary.

During 2023, the ALMA Scorecard was updated to include a new indicator reporting on whether a country has launched their national End Malaria and NTD Council (see Multisectoral Advocacy, Action and Resource Mobilisation for more information). This indicator was added to reflect the AU Assembly Decision calling for all malaria-endemic countries to establish a council or fund. Global Fund malaria allocations were also included, to ensure that countries prioritised malaria in their funding applications. Actions taken by countries and their partners, resulting from the use of the scorecard in 2023 include the commitment of increased resources, accelerated procurement to fill gaps and acceleration of campaigns.

Regional Scorecards

The Regional Economic Communities (RECs) continue to implement regional malaria scorecards to strengthen cross-border accountability and action. These scorecards are produced for REC leadership, Heads of State and Government, Ministers, and other partners. To date, four of the RECs have launched regional scorecards.

Regional Scorecard Highlights (2023)

- East African Community (EAC): The Great Lakes Malaria Initiative scorecard is produced and updated quarterly and presented during the Health Ministers’ meeting, and regional partners meeting with the EAC Secretary General.

- Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS): Launched their regional scorecard with partners in August 2023.

- Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS): ECOWAS/WAHO finalised the regional scorecard for West Africa. This scorecard will be used in high-level meetings to drive accountability and action. Likewise, the Sahel Malaria Elimination Initiative (SaME) scorecard was updated to align with the SaME strategic plan following a technical meeting in March 2023.

- Southern African Development Community (SADC): Developed the regional malaria scorecard in September 2023 aligned with the region’s malaria strategic plan and included the scorecard in SADC’s annual malaria report. The Elimination 8 scorecard continues to be updated and used in high-level ministerial forums of the E8 countries.

National Scorecard Tools

More than 40 countries across the region continued implementing national malaria, RMNCAH, Nutrition, NTD and community scorecard tools to drive accountability and action at all levels of the health system. Scorecard tools monitor priority indicators, tracking progress, identifying bottlenecks, enhancing accountability and driving action. To date, 41 countries across the region have developed malaria scorecards, 31 countries have developed RMNCAH scorecards, 18 have developed NTD scorecards, and 4 have developed nutrition scorecards.

Member States continue to strengthen and institutionalise their scorecard management tools. In 2023, countries continued to conduct self-assessments of their use of scorecard management tools using the scorecard maturity framework. This framework enables countries to identify actions to take to strengthen their national scorecards and institutionalise these tools. As a result of progress made by several countries, including for NTDs and RMNCAH, ALMA has introduced a new maturity level in 2023 to increase support for high-level political engagement, incorporation of scorecards into pre-service and in-service training for health workers, inclusion of scorecard tools into routine supervision and staff terms of reference.

Actions taken as a result of scorecard tool in 2023 use include training and mentoring of health staff, increased resources to support underperforming interventions, including stockouts, support to enhance data quality and timeliness and community engagement and SBC to enhance uptake of service.27

Community Scorecards

Community engagement and ownership of health is key to achieving Africa’s health targets. Several Member States are implementing community scorecards to collect quarterly feedback directly from community members on the quality and accessibility of health services. Community scorecards create a space for community dialogue to identify systemic challenges in accessing essential health services and to develop action plans to address the issues identified by citizens. The community data are used to create colour-coded scorecards, providing important insight directly from users of health services. In some countries, like Ghana, the community scorecard is used by local government to allocate resources to community action plans. As a result of the community scorecard process, countries have renovated and constructed health facilities, acquired land for facilities, resolved issues of water scarcity and distribution, constructed health facility washrooms and structures for community health workers and midwives, addressed medicine stock out issues through local initiatives and more.

ALMA Scorecard Hub

ALMA’s Scorecard Hub is an online platform that enables countries to share their national scorecards, publish best practices, and access trainings and toolkits. The scorecard hub continues to grow a community of practice to document country and partner innovations and support collaboration and knowledge sharing via webinars.

2023 ALMA Joyce Kafanabo Awards

During the 2023 AU Summit, 7 Member States were recognised by His Excellency Umaro Sissoco Embaló for their use of scorecard management tools to strengthen the malaria and NTD response and improve RMNCAH and community health.

Zambia: Best Malaria Scorecard Tool: Zambia decentralised their malaria scorecard and use the Scorecard Web Platform Workplan Manager to provide their National Malaria Elimination Programme and national End Malaria Council with access to real-time information for decision making. This has led to a significant increase in meeting the operational plan implementation targets. The scorecard is used for monthly data reviews in each province.

Kenya: Best RMNCAH Scorecard Tools: Kenya decentralised their RMNCAH scorecard to county-level and shares the scorecard with key country partners at national, county and health facility levels. At the county-level, the scorecard is used extensively in existing accountability mechanisms including county performance review meetings and sub-county data review meetings. In these meetings, the scorecard is reviewed, and actions are generated and entered into the Scorecard Web Platform’s Action Tracker.

Republic of Congo: Best NTD Scorecard Tool: Congo uses their NTD scorecard tool to help with collaboration and coordination of national stakeholders, monitoring the implementation of interventions, identifying service bottlenecks and national priorities and stimulating action. The scorecard identified gaps leading to resource commitments from the government.

Ethiopia: Best Community Scorecard: Ethiopia uses their community scorecard tool to enhance community ownership and engagement in their own health. It is used to mobilise technical and financial support, including increased contributions from community members, partners and government.

Rwanda: Best Institutionalisation of Scorecard Tools: Rwanda has integrated their malaria and NTD scorecards and included them in their national strategic plan as key performance and management tools to track progress of indicators linked to their priorities. The scorecards are discussed at the technical working groups with various partners and stakeholders to identify underperformance and develop actions to improve. They have also been used to help co-ordinate local NGO support to community mobilisation and engagement.

Ghana: Best Innovative Use of Scorecard Tools: Ghana is the first country to include quality of care community-generated data from the community scorecard tool into DHIS2. Through this, more stakeholders can access community data and it can be aggregated to sub-district, district, regional and national level. Significant action and resource mobilisation by communities and their partners has also been documented through this process. The country trained members of parliament on how to access routine health data through malaria, RMNCAH, nutrition and community scorecards to enhance visibility and resource mobilisation.

Tanzania: Best Innovative Use of Scorecard Tools: Tanzania trained members of parliament on how to access malaria and other health data through scorecards. Tanzania further decentralized its scorecard by training decision-makers and health teams in high-burden regions on how to use the scorecard data to drive action, accountability, and advocacy.

Multisectoral Advocacy, Action & Resource Mobilisation

Zero Malaria Starts with Me

Launched in 2018, the “Zero Malaria Starts with Me” campaign is a multisectoral initiative designed to mainstream ownership of malaria across all sectors. The campaign is organised around three pillars:

- Advocacy to maintain malaria high on the national development agenda

- Increased domestic funding for malaria, including from the private sector

- Expanded community engagement on health and ownership of malaria outcomes

During 2023, the African Union Commission, RBM Partnership to End Malaria, ALMA, Speak Up Africa, Global Fund, and Republic of Senegal convened the “Zero Malaria Starts with Me Fifth Anniversary High-level Ceremony.” This event amplified the visibility of the Zero Malaria Starts with Me campaign, provided an opportunity to share successes and best practices, discuss challenges, and resulted in the announcement of the AU Youth Declaration on Malaria Elimination.

National Campaigns

The Heads of State and Government of the African Union called for malaria-endemic countries to accelerate the launch of national Zero Malaria Starts with Me campaigns. To date, 28 countries have launched Zero Malaria Starts with Me campaigns, including Angola, Benin and Togo during 2023.

National Campaign Examples (2023)

- Benin: Supported a series of multisectoral advocacy initiatives that resulted in a 60% increase to the national budget for malaria.

- Ghana: Established a Parliamentary Malaria Caucus to strengthen political commitment to malaria elimination.

- Sierra Leone: Engaged parliamentarians to sign a declaration supporting increasing the national health budget to 15% of government spending (in line with the 2001 Abuja Declaration). Partnered with top musicians to produce an original song to spread key malaria messaging and build momentum for the Zero Malaria movement. Launched the Malaria Media Coalition with journalists leading to a six-fold increase in media coverage.

Zero Malaria Business Leadership Initiative

Launched in 2020 by the Ecobank Group in partnership with the RBM Partnership to End Malaria and Speak Up Africa, the Zero Malaria Business Leadership Initiative (ZMBLI) aims to stimulate private sector engagement in the fight against malaria in Africa. Since launching, ZMBLI has mobilised $5.9 million USD from 59 companies across Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Senegal, and Uganda. Senegal’s ZMBLI campaign mobilised $1 million USD to procure motorbikes to enable health workers to access hard-to-reach regions.

Zero Malaria Football Club

Zero Malaria F.C. is a squad of globally renowned footballers joining forces to end malaria. Led by co-captains Luis Figo and Khalilou Fadiga, the team aims to increase awareness of the disease, communicate the need for urgent action, and increase pressure on policymakers to act.

End Malaria Councils and Funds

National End Malaria Councils and Funds are multisectoral bodies promoting advocacy, action, resource mobilisation, and accountability for the fight against malaria.28 These councils are country-owned and country-led. Their members are senior leaders drawn from the Public Sector, Private Sector, Civil Society and Communities. To date, councils have been launched or announced in 13 countries, including Guinea-Bissau (launched), Tanzania (launched), Guinea (announced) in 2023. 8 additional countries initiated or made progress in the planning for a council in 2023.

Councils enable national programmes and their partners to access untapped capabilities, assets, and resources to combat malaria. To date, more than $50 million USD has been mobilised by EMCs.

Action and Resource Mobilisation Examples (2023)

- First Quantum Minerals invested $6 million in Zambia to support the implementation of vector control and case management programmes in partnership with the National Malaria Elimination Programme.

- Zambia’s EMC has secured $6 million USD from the Rotarian Malaria Partners to support community health workers (CHWs) and is mobilising bicycles for CHWs

- Eswatini’s End Malaria Fund procured preventative medicines on behalf of the Ministry of Health to ensure adequate coverage during the 2022/23 malaria season.

- Kenya and Tanzania’s EMCs entered into memoranda of understanding with SC Johnson to provide $3.4 million USD to support the construction of health clinics, communications campaigns, and vector control interventions.

- Malaria Free Uganda is finalising Memoranda of Understanding with 28 companies to contribute financial and in-kind resources (e.g., Next Media to broadcast television, radio, and digital advertising)`.

- Mozambique’s Fundo da Malaria mobilised financial and in-kind resources, including ITNs, for emergency distribution.

EMCs also facilitate multisectoral national advocacy campaigns (e.g., Zero Malaria Starts with Me) and engage community leaders to champion ending malaria. EMCs often include religious and traditional leaders, celebrities, and other advocates. This raises the visibility of malaria at the national and subnational levels and promotes community ownership.

Advocacy Examples (2023)

- Zambia’s End Malaria Council led inter-faith advocacy through the Faith Leaders Advocating for Malaria Elimination (FLAME) initiative, including distributing malaria messaging through 1,000 religious leaders and on television and radio, engaging national leaders, and organised malaria conferences.

- Mozambique’s Fundo da Malaria met with the parliamentary forum on malaria, which was launched by the Fund in 2022. MPs received status updates on malaria and the major gaps and bottlenecks.

- The Nigeria EMC launched a national communications campaign targeting women to promote accessing antenatal care and IPTp services and encourage the use of long-lasting insecticide-treated mosquito nets. Religious leaders also launched a campaign to train clergy on malaria advocacy and social and behaviour change communications.

- Malaria Free Uganda conducted a mass media campaign with private sector messages committing to the fight against malaria and encouraging others to join them.

Parliamentarians

Members of Parliament can play an important role in ending malaria. As community leaders, they can lead community engagement and advocacy within their constituencies. At the national level, they can advocate for increased funding for health and malaria, and lead policymaking efforts to reduce barriers to malaria control and elimination. Committees on Health can promote accountability and action. Several countries have established parliamentary forums and interest groups to sensitise lawmakers (e.g., Uganda Parliamentary Forum on Malaria, Tanzania Parliamentary Alliance Against Malaria, Mozambique Malaria Parliamentary Forum). Regional engagement of parliamentarians is also a priority to share best practices and build cross-border relationships. At continental-level, the Pan-African Parliament is actively engaged in a mapping exercise to mobilize additional national resources for combating HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Parliamentarian Examples (2023)

- The Uganda Parliamentary Forum on Malaria (UPFM) participated in an anti-malaria walk to commemorate World Malaria Day. UPFM advocated for 10% of the national health budget to be allocated for malaria. WHO, the Ministry of Health, and UPFM hosted a dialogue to discuss the role that parliamentarians can play.

- Ghana’s parliamentary caucus advocated for increased funding, resulting in IRS being extended to 2 additional regions.

- Parliamentarians participated in the CS4ME29 annual forum

Youth

In line with the African Union agenda that recognizes the importance of youth participation, involvement, and representation in the development of the continent, ALMA recruited more than 3,000 ALMA youth champions across Africa and the diaspora from existing leadership positions across all sectors to mobilise youth-driven advocacy and solutions for ending malaria, neglected tropical diseases and promoting universal health coverage (UHC). The ALMA Youth Advisory Council (AYAC), composed of 11 young leaders, provides strategic guidance on engaging young people in the fight against malaria and UHC. In July 2023, at the Zero Malaria Starts with Me 5th Anniversary Ceremony in Senegal, the AYAC joined 100 young people to launch the Zero Malaria Starts with Me Youth Declaration.

Member States continue to launch National Malaria Youth Corps (NMYC). NMYC convene and organise Youth leaders to promote advocacy, action and accountability for malaria and UHC. To date, four countries have launched NMYC (Kenya, Eswatini, Mozambique and Zambia). During 2023, Congo and Cameroon endorsed the establishment of NMYCs with preparations underway for official launches, and other countries included NMYCs in their Global Fund grant applications.

Illustrative Youth Activities (2023)

- AYAC amplified youth voices and called for more action to end NTDs and empowering women innovators working end malaria through social media platforms on World NTD Day and International Women’s Day.

- On the World Malaria Day 2023, French and English podcasts were released by AYAC and NMYCs. AYAC members also hosted a Twitter Spaces live discussion on ending malaria and UHC.

- ALMA published four Youth stories under the banner of “My Zero Malaria Story” and made an announcement for the open call for essay submissions.

- AYAC’s Chair took over the Twitter account of Trevor Mundel (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s Global Health President) for World Malaria Day to highlight the importance of innovation in identifying and responding to new cases quickly and new types of insecticide-treated nets. The youth council chairperson also recognized the power of convening youth champions across the continent to help eliminate malaria by 2030.

- On International Youth Day, ALMA and the Ifakara Health Institute announced the 3 winners of the Malaria Innovation Essay Competition for African Youth. These were selected from the 685 essays submitted.

Regional and Cross-border Coordination

Regional Economic Communities

The Regional Economic Communities (RECs) are regional groupings of African states and are the pillars of the Africa Union. RECs facilitate regional economic integration between members of the individual regions and through the wider African Economic Community. RECs provide a mechanism for joint planning, implementation and monitoring of activities, as well as policy harmonisation and economic integration. Under the guidance of the African Heads of State & Government, the RECs have adopted malaria as a priority issue—mainstreaming malaria into high-level political and technical forums and developed regional malaria scorecards30 and strategic plans.

Cross-border Coordination

Member States continue to expand bi-lateral and multi-lateral, cross-border cooperation and coordination on malaria interventions. These activities strengthen planning and strategic alignment between national malaria programmes and sharing of data and best practices. Cross-border coordination is also essential to reaching underserved communities in border areas. Member States report that limited funding and human resources constrains their ability to expand cross-border activities.

Example Cross-border Activities (2023)

- Zambia hosted a joint data review and planning meetings with neighbouring countries to align malaria interventions and address the cross-border risk of malaria.

- The Isdell:Flowers Cross Border Malaria Initiative, a philanthropic initiative, works with national malaria programmes and 1,500 community health workers to support malaria testing and treatment, communications, and health clinics in border regions between Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

- Countries across the Sahel continue to implement regional Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention for children under 5.

- Senegal and The Gambia coordinate disease and vector surveillance and the distribution of LLINs and other vector control initiatives in border areas.

- Senegal and Guinea-Bissau are implementing cross-border, community-based case management.

- Public and private resources continue to be channelled through the MOSASWA/LSDI2 mechanism to support malaria interventions in South Africa, Eswatini, and Mozambique.

Coordination on Health Commodities (including malaria)

African Medicines Agency

The African Medicines Agency (AMA) Treaty came into effect in 2021. The AMA provides a mechanism for countries to pool resources for improving access to quality, safe and efficacious medical products in Africa. To date, 27 countries have ratified and 10 additional countries have signed the treaty, with all countries urged to ratify. The AMA Board has been appointed and Rwanda has agreed to be the host country.

Registration of Vector Control Products

Next-generation malaria commodities that address biological and environmental threats have been developed and endorsed by WHO.31 However, getting these new tools and commodities to end users as quickly as possible will require removing in-country registration bottlenecks, such as unclear responsibilities and duplication of in-country trials. Actions to consider would include the new WHO collaborative procedures for registration of vector control products or regional harmonization of registration. From a recent survey on vector control products registration landscape in Africa, registration of nets in countries was solely based on WHO recommendations. This is the same approach used for registration of medicines, vaccines, and diagnostics in countries. In view of this situation, it is recommended that countries adopt a comprehensive registration of vector control products, including the WHO collaborative registration procedures and the regional harmonized approach to vector control registration. Countries also need to build capacity within national regulatory authorities for the adoption of new tools/products for vector control.

Local Manufacturing

Despite accounting for 96% of global malaria cases and deaths, less than 2% of malaria commodities are manufactured in Africa. Africa’s over-reliance on imported health products is a pressing concern for the continent. Recent events have demonstrated that without access to health products, people are susceptible to diseases including malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Local manufacturing is vital to ensuring affordability and accessibility. It is also a key driver for stimulating economic development and long-term sustainability on the continent.

Actions to Promote Local Manufacturing (2023)

- Ongoing facilitation of North-South technology transfer to produce novel second-generation nets.

- To strengthen harmonization of vector control registration processes and facilitate engagement with RECs and national regulatory authorities, WHO hosted a stakeholder workshop on the Collaborative Registration Procedure of Vector Control Products. A joint consultation on registration of vector control products was also organized with AUC, NEPAD and Innovation to Impact.

- ALMA and Africa CDC advocated for sustained support for the AU’s Agenda 2063 and NEPAD’s Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa among African Heads of State. Priorities include greater investment for the discovery and development of new tools (building resilience and preparedness to future pandemics), supporting the creation of African pooled procurement purchasing platforms, and seeking commitments from external donors and our governments to procure a minimum percentage of commodities from African manufacturers.

Progress on Neglected Tropical Diseases

Digitalisation

ALMA Scorecard for Accountability & Action

Workshops and consultations have been conducted to identify additional NTD indicators to add to the ALMA Scorecard for Accountability & Action. During the 14th NTD NGO Network Conference, more than 100 stakeholders from Member States and partners32 participated in brainstorming sessions to identify data availability and potential indicators.

National NTDs Scorecards

18 countries have developed national NTDs scorecards, including two new countries (Burundi and Nigeria) in 2023. Several of these countries conducted NTD scorecard indicator review and started the decentralization of NTD scorecards down to district-level (i.e., Congo, Gambia, Niger, Senegal, Tanzania, and Zambia) and others conducted scorecard indicator review and trained the trainers to lead the decentralization of NTD scorecard (i.e., Botswana, Burkina Faso, and Guinea).

Example Actions Taken on NTDs (2023)

- Burkina Faso, The Republics of Congo and Rwanda used their scorecards to identify the areas of underperformance and conduct formative supervisions accordingly.

- The Gambia, The Republics of Congo and Senegal mobilised resources to cover the gaps identified while analysing the scorecard.

10 countries are publicly sharing their NTD scorecard online via the ALMA Scorecard Hub (i.e., Burundi, Burkina Faso, Congo, Gambia, Guinea, Senegal, Zambia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Malawi). 2 countries have also documented and published the NTD scorecard best practices documentation (Niger and Rwanda). Additionally, countries with NTDs scorecards universally enhanced NTD data quality and availability by adding additional indicators into DHIS2.

Multisectoral Advocacy, Action & Resource Mobilisation

Building on the success of national End Malaria Councils, a number of countries are launching joint malaria & NTDs councils or integrating NTDs into existing EMCs. In May 2023, Guinea-Bissau was the first country to launch a national End Malaria & NTDs Council. Botswana, Rwanda, South Africa, South Sudan continue to plan to launch joint malaria and NTDs councils and funds.

End Malaria & NTDs Councils and Funds adapt the approach of EMCs to mobilise advocacy, action and resources to support both disease areas. The inclusion of NTDs promotes integration, sharing of resources, and a harmonised approach for engaging sectors to mobilise financial and in-kind resources.

Regional Coordination

ALMA and various NTDs partners participated in the Regional NTD meeting for EAC and ECCAS. This meeting provided an opportunity to review the progress achieved by countries in the fight against NTDs and to advocate for increased domestic resources and improved NTDs data for evidence-based decision.

Glossary

ACT

Artemisinin-Combination Therapy

ALMA

African Leaders Malaria Alliance

AMA

African Medical Agency

AYAC

ALMA Youth Advisory Council

CHW

Community Health Worker

EMC / EMF

End Malaria Council or End Malaria Fund

HBHI

High Burden to High Impact

IDA

World Bank International Development Association

IRS

Indoor Residual Spraying

ITN

Insecticide-treated Net

NTD

Neglected Tropical Disease

NMYC

National Malaria Youth Corps

RMNCAH

Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, Child and Adolescent Health

RDT

Rapid Diagnostic Test

REC

Regional Economic Community

ZMBLI

Zero Malaria Business Leadership Initiative

Acknowledgements

This report has been prepared by the African Union Commission, African Leaders Malaria Alliance and RBM Partnership to End Malaria. The drafting and revisions of this report include contributions from national malaria control programmes, development partners, and other stakeholders from across the continent and the global community.

Special Thanks

- Sheila Tamara Shawa-Musonda (AUC)

- Hiba Boujnah (AUC)

- Eric Junior Wagobera (AUC)

- Jeremy Ouedraogo (AUDA-NEPAD)

- Barbara Glover (AUDA-NEPAD)

- Chris Okonji (AUDA-NEPAD)

- Jackson Sophianu Sillah (WHO AFRO)

- Fernanda Francisco Guimarães (Angola)

- Sidzabda Christian Bernard Kompaore (Burkina Faso)

- Landrine Mugisha (Burundi)

- Marcellin Joël Ateba (Cameroon)

- Aboudou Rahime Naili Bourhane (Comoros)

- Hadjira Abdullatif (Comoros)

- Gudissa Assefa (Ethiopia)

- Andy Igouwe (Gabon)

- Paul Boateng (Ghana)

- José Ernesto Nante (Guinea-Bissau)

- Lumbani Munthali (Malawi)

- Samira Guina Salomão Sibindy (Mozambique)

- Godwin Ntadom (Nigeria)

- Michee Kabera Semugunzu (Rwanda)

- Sene Doudou (Senegal)

- Pai Elia Chambongo (Tanznaia)

- Busiku Hamainza (Zambia)

- Melanie Renshaw (ALMA)

- Stephen Rooke (ALMA)

- Monique Murindahabi (ALMA)

- Abraham Mnzava (ALMA)

- Foluke Olusegun (ALMA)

- Tawanda Chisango (ALMA)

- Samson Katikiti (ALMA)

- Angus Spiers (I2I)

- James Wallen (Speak Up Africa)

- Aloyce P. Urassa (AYAC)

- John Kamau Mwangu (AYAC)

Footnotes

- WHO, World Malaria Report 2023 (note that 2022 is the most recent year for which data is publicly available). ↩︎

- AU, Catalytic Framework to End AIDS, TB and Eliminate Malaria. ↩︎

- Ethiopia, The Gambia, Ghana, Rwanda, Togo, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Additionally, Algeria, Cabo Verde, Egypt, Morocco have all eliminated malaria or reported no malaria cases or deaths (Cabo Verde is in the final stages of being certified as having eliminated malaria). 20 Member States reduced incidence by> 10% and 23 reduced incidence by >23%. WHO, World Malaria Report 2023. ↩︎

- WHO, Guidance for Malaria: Pyrethroid-chlorfenapyr ITNs for prevention of malaria vs Pyrethroid-only ITNs for prevention of malaria, MAGICapp (2023). ↩︎

- Three-year study of net effectiveness conducted in Tanzania. Results showed that PBO nets were 13% more effective versus 39% for Pyrethroid-chlorfenapyr nets. Jacklin F. Mosha et al., Effectiveness of long-lasting insecticidal nets with pyriproxyfen–pyrethroid, chlorfenapyr–pyrethroid, or piperonyl butoxide–pyrethroid versus pyrethroid only against malaria in Tanzania: final-year results of a four-arm, single-blind, cluster-randomised trial (Sept. 2023). ↩︎

- WHO, News release: WHO recommends R21/Matrix-M vaccine for malaria prevention in updated advice on immunization (Sept. 2023). ↩︎

- The two vaccines have not been tested in direct comparison studies, and R21/Matrix-M has not been tested in areas of high, perennial transmission. Given the similarity of the vaccines and that RTS,S is efficacious in high, moderate and low transmission settings, however, it is likely that R21 will also be efficacious in all malaria endemic settings. ↩︎

- This analysis was based on the submissions by Member States during the first two windows of the GF7 grant applications in 2023. ↩︎

- See sections on insecticide resistance and drug resistance. ↩︎

- During the early stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic, WHO estimated that malaria deaths could double if essential malaria services were disrupted. This scenario was avoided due to the prioritisation of malaria interventions by Member States despite lockdowns and other disruptions. ↩︎

- WHO, Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016-2030 (2021 Update), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031357. ↩︎

- World Bank, Africa Pulse: Delivering Growth to People Through Better Jobs, No. 28(Oct. 2023). ↩︎

- WHO, World Malaria Report 2023. ↩︎

- See, e.g., WMO, Africa Suffers Disproportionately from Climate Change (Sept. 2023); IMF, Africa’s Fragile States Are Greatest Climate Change Casualties (Aug. 2023); African Development Bank, Climate Change in Africa: Africa, Despite Its Low Contribution to Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Remains the Most Vulnerable Continent (Dec. 2019). ↩︎

- IPCC, Sixth Assessment Report, Ch. 9 (2022). ↩︎

- WMO, Africa Suffers Disproportionately from Climate Change (Sept. 2023). ↩︎

- EM-DAT (2023). ↩︎

- EM-DAT (2023). ↩︎

- Dr. Marina Romanello et al., The 2022 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Health at the Mercy of Fossil Fuels (Oct. 2022). ↩︎

- Sadie J. Ryan et al., Shifting Transmission Risk for Malaria in Africa with Climate Change: A Framework for Planning and Intervention, Malaria J. (May 2020). ↩︎

- See ALMA Scorecard for Accountability & Action in annex. ↩︎

- Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060265. ↩︎

- A. Mnzava et al, Anopheles stephensi in Africa requires a more integrated response, Malaria J. 21(1)(May 2022); W. Takken & S. Lindsay, Increased Threat of Urban Malaria from Anopheles stephensi Mosquitoes, Africa, Emerg. Infect. Dis. 25(7) (Jul. 2019). ↩︎

- WHO, Initiative to Stop the Spread of Anopheles stephensi in Africa (Updated 2023). ↩︎

- WHO, World Malaria Report 2023. ↩︎

- During 2023, the African Union Commission developed a framework to integrate health security, emergency preparedness & response, resilient and sustainable health systems, and UHC into the humanitarian, development and peace nexus. This framework will be announced on the sides of the 2024 AU Summit. ↩︎

- Case studies and best practices are documented on the ALMA Scorecard Hub. ↩︎

- Several Member States are exploring opportunities to launch councils and funds to support both malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases. Existing councils are also considering expanding their mandate to include NTDs. ↩︎

- CS4ME is a coalition of more than 600 civil society organisations advocating for and supporting efforts to control and eliminate malaria. ↩︎

- See Regional Malaria Scorecards under Digitalisation. ↩︎

- See Expanded Malaria Toolkit. ↩︎

- E.g., WHO, Uniting to Combat NTDs, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, AMREF, GLIDE, The END Fund, CIFF. ↩︎