Foreword

African Union Member States account for the vast majority of global malaria cases (96%) and deaths (97%), and overall progress remains stalled. Incidence and mortality have plateaued in most countries, and only 3 are on track to achieve the 2025 targets of the Catalytic Framework to End AIDS, TB and Eliminate Malaria in Africa. Behind these figures lies a stark truth: we remain off-course and the “perfect storm” of threats has intensified. Member States are now contending with significant funding volatility, including a decline in Official Development Assistance and a shortfall in the Eighth Replenishment of the Global Fund. This fiscal contraction coincides with the escalation of biological threats (e.g., insecticide and drug resistance) and the impact of climate change. If left unaddressed, a 30% reduction in malaria funding will result in 146 million additional malaria cases and 397,000 preventable deaths by 2030, with profound consequences for Africa’s human capital, economic growth, and social stability—Member States stand to lose an estimated $37 billion in GDP.

At the African Union Summit in 2025, Heads of State and Government endorsed the African Union Roadmap to 2030 & Beyond: Sustaining the AIDS Response, Ensuring Systems Strengthening and Health Security for the Development of Africa. This Roadmap affirms that health sovereignty and domestic resource mobilisation are central to our collective future. It calls for integrated, people-centred health systems, stronger surveillance, and sustained investment in primary health care and universal health coverage, with malaria as a core entry point.

Throughout 2025, these commitments were reinforced on regional and global stages—from the World Health Assembly and the WHO Regional Committee for Africa to the Abuja “Big Push” meeting and high-level events during the United Nations General Assembly. Leaders across Africa spoke with one voice: malaria must be treated as a national development and security priority. We underscored the need to fully replenish the Global Fund and Gavi, to leverage the World Bank International Development Association and climate financing, and to protect and expand domestic allocations for health.

Member States are expanding national health budgets (including dedicated budget lines), establishing and strengthening End Malaria and NTD Councils and Funds, and piloting innovative financing mechanisms. Regional Economic Communities (RECs) are harmonising policies, supporting pooled procurement, and promoting local manufacturing. Parliamentarians, government line ministries, civil society, faith leaders, the private sector, and youth coalitions are working together to keep malaria high on the political agenda, mobilise resources, and ensure accountability for results.

At the same time, the malaria toolkit has never been stronger. Countries are rapidly rolling out dual active-ingredient insecticide-treated nets, expanding access to malaria vaccines for children, scaling up seasonal and perennial chemoprevention, strengthening community-based case management, and rolling out new tools such as spatial repellents. Investment in digital health, climate-informed surveillance, and national malaria data repositories is enabling more timely, sub-nationally tailored responses. Scorecard tools—from community to continental level—are turning data into action, helping leaders target scarce resources where they will have the greatest impact.

Africa is positioning itself as a producer of essential health commodities with support from the African Medicines Agency, Africa CDC, AUDA-NEPAD, and RECs—enhancing self-reliance and resilience. A dynamic pipeline of new vaccines, antimalarial medicines, diagnostics, and vector control products will accelerate the big push towards malaria elimination.

This African Union Malaria Progress Report 2025 is documents the risks of retreat at a moment of constrained financing and intensifying threats, but it also demonstrates that we can still bend the curve towards elimination with determined leadership, smart use of data, and sustained investment. The choices we make on enhanced domestic resource mobilisation, on global solidarity, on innovation and local production, and on protecting the most vulnerable will ensure that malaria is finally consigned to history.

We therefore issue a clear call to action. We urge all Member States to treat malaria as a central pillar of health sovereignty and economic transformation, to protect and increase domestic and external funding, and to fully implement the priorities of the catalytic framework and the “Big Push” Against Malaria. We call on our international partners to stand with Africa at this critical moment—fulfilling commitments, aligning support with national strategies, and investing in the tools and systems that will secure a malaria-free future. The path ahead is challenging, but it is within our power. If we act now, together, with unwavering resolve, we can safeguard our people, strengthen our economies, and ensure that future generations grow up free from the threat of malaria.

H.E. Mahmoud Ali Youssouf

Chair, African Union Commission

President Advocate Duma Gideon Boko

Republic of Botswana

ALMA chair

Dr. Michael Adekunle Charles

Chief Executive Officer, RBM Partnership to End Malaria

1. Progress Against the AU Catalytic Framework Targets for Malaria Elimination

1.1 Member States are not on track to achieve targets

According to the WHO, there were 270.8 million malaria cases (96% of global total) and 594,119 deaths (97% of global total) in AU Member States in 2024.1 Progress toward malaria elimination remains stalled since 2015 and Africa as a whole is not on track to achieve its goals of eliminating malaria by 2030. Among the malaria-endemic Member States, 11 have achieved the 2020 goal of reducing malaria incidence and mortality by 40% and 5 are on track to achieve the 2025 target of a 75% reduction.2 This stagnation occurs despite the progress made in the global fight against malaria since 2000, preventing 1.64 billion cases and saving 12.4 million lives in Africa.3

Member States On-Track to Achieve 2025 Target4

- Incidence: Rwanda, South Africa, Zimbabwe

- Mortality: Botswana, Eswatini, South Africa, Zimbabwe

1.2 Member States are deploying a broader malaria toolkit

During 2025, Member States continued to rapidly scale up a growing set of tools and approaches for combatting malaria.

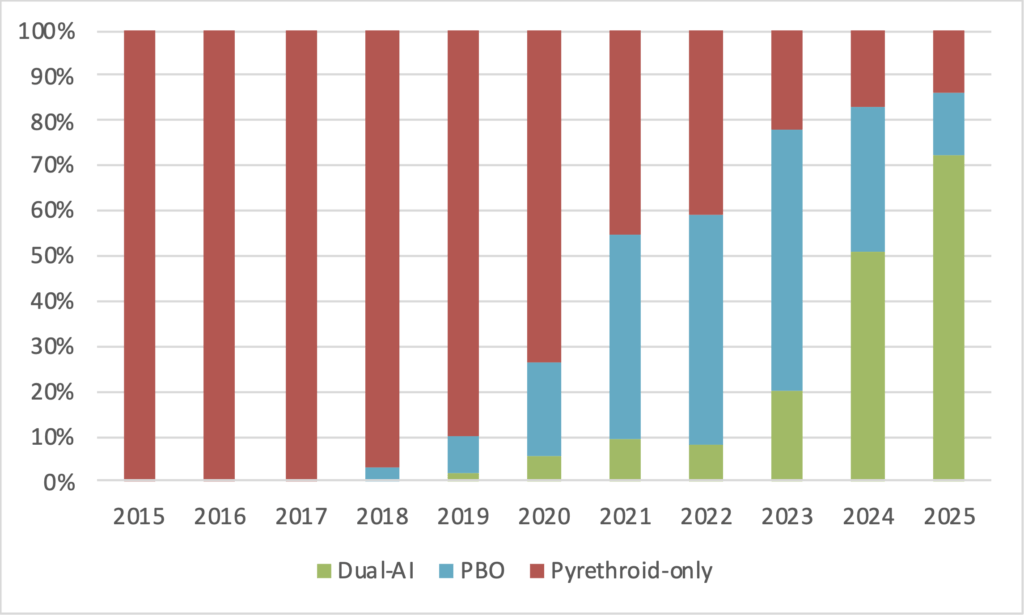

- Dual AI Nets: Member States are expanding the use of dual active-ingredient (pyrethroid-chlorfenapyr) ITNs. These next-generation nets address the threat of insecticide resistance and can reduce the malaria burden by over 45% compared to pyrethroid-only nets.5 74% of the ITNs distributed across 39 Member States in 2025 were dual-AI nets (up from 20% in 2023 and 51% in 2024).6

- Vaccines: 24 countries7 have introduced WHO approved malaria vaccines8 28.3 million doses of WHO approved malaria vaccines were distributed in 2025, up from 10.5 million doses in 2024).9

- Spatial Repellants: WHO prequalified two spatial repellants in 2025, which have begun to roll out as a complement to IRS and ITNs.

- Seasonal and Perennial Malaria Chemoprevention: A record 22 countries planned to implement SMC in 2025 and several countries are developing strategies and deploying PMC (e.g., Nigeria).10

1.3 The “Perfect Storm” continues to intensify and threatens to set back progress against malaria significantly

The 2024 Malaria Progress Report called attention to “a perfect storm of converging crises that threaten to derail decades of progress against the disease.” The challenges Member States face continue to intensify—especially the gaps in the resources necessary to sustain malaria interventions. Without urgent action by Member States and the global community to sustain malaria resources, a rapid resurgence of cases and deaths is expected which will significantly impact health systems and economies.

1.3.1 Declining Funding and Complex Fiscal Environments

Already under financial stress,11 Member States’ capacity to accelerate progress against malaria was limited by declining funding in 2025. Official Development Assistance declined by 21% in 2025 as several donor countries reduced and redirected bilateral and multilateral support.

- Unfulfilled commitments and funding shortfalls resulted in the Global Fund reducing existing (GC7) grants by 11%.

- The closing of the US Agency for International Development and subsequent restructuring of the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) resulted in sudden and unexpected operational gaps across the 24 supported Member States. Funding uncertainties delayed procurement and distribution of malaria commodities12 and negatively impacted the capacity of Member States to plan for activities. The stop work order resulted in a loss of skilled staff and partner experts.

The funding environment is expected to remain constrained in the coming years as funding is cut from key donors.

- The US Government will continue to provide funding through the State Department, but bi-lateral funding will decline over the next 3-5 years as determined in newly negotiated bilateral Memorandums of Understanding.

- The Eighth Replenishment of the Global Fund (2027-2029) mobilised approximately $12.9 billion13 in pledged resources to support countries by December, short of the $18 billion target. This presents an urgent risk as the Global Fund provides almost 60% of financing for malaria programming and has been instrumental for countries have access to life-saving interventions.

- Several Member States have actively stepped in to fill the funding gap, but malaria is concentrated in the lowest-income countries resulting in limited fiscal space to replace significant decreases in ODA and the Global Fund.

A 30% reduction in funding is expected to result in a 640 million fewer ITNs, 146 million additional cases, 397,000 additional deaths (75% children under 5), and a loss of $37 billion in GDP by 2030.

1.3.2 Humanitarian Emergencies

Malaria is concentrated in countries impacted by humanitarian crises. Internally displaced populations, cross-border movement of refugees, and disruptions to supply chains and health services contribute to significant increases in malaria cases and deaths. Humanitarian crises also lead to significant increases in delivery and implementation costs, further exacerbating funding gaps. The number of displaced persons in Africa increased from 9.1 million in 2009 to 45 million in 2024 with 83% of refugees and 40% of IDPs concentrated in rural areas where the risk of malaria is the highest.14

1.3.3 Biological Threats

Insecticide, drug and parasite resistance continues to grow. Member States are accelerating the transition to next-generation insecticides and rapid diagnostic tests (i.e., to address the HRP2/3 gene deletion) and new medicines are rolling out to address partial drug resistance, but at higher costs. 74% of nets distributed in Africa in 2025 were dual-AI nets, a rapid scaling up to address resistance.

Thirty-eight Member States have reported resistance to three or more classes of insecticides since 2010. Insecticide resistance significantly reduces the efficacy of certain vector control interventions (e.g., pyrethroid-only ITNs), contributing to the plateauing in malaria incidence observed over the past decade.

Additionally, the invasive An. stephensi mosquito, which can transmit malaria in urban areas, has been documented in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana and Niger.

1.3.4 Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events

Climate change continues to make malaria more unpredictable and difficult to control, especially when coupled with intervention gaps. Flooding and higher temperatures contribute to malaria upsurges and increased burdens on already strained health systems. Southern Africa in particular experienced increased rainfall in 2025 leading to increases in malaria (e.g., Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe). Climate-related upsurges drive increased pressure on the availability of diagnostic tests, antimalarial medicines, and vector control interventions—resulting in increased stockouts.

1.3.5 Increasing Costs

As the population of Africa continues to grow (doubling since 2000), the resources required to prevent, test, and treat malaria increases. Member States report facing significantly higher commodity needs and operational costs. The growth in costs is further exacerbated by the higher cost of new commodities. While Member States are undertaking subnational stratification and improved targeting of resources, sustaining coverage of malaria interventions is becoming more challenging and requires urgent action and resource mobilisation.

2. Accelerating Progress to Achieve the AU Catalytic Framework Targets

Africa remains off track to achieving the targets of the Catalytic Framework to End HIV, TB and Eliminate Malaria in Africa by 2030. In response, the Heads of State and Government of Africa endorsed the African Union Roadmap to 2030 & Beyond: Sustaining the AIDS Response, Ensuring Systems Strengthening and Health Security for the Development of Africa15 to accelerate action. Member States and their partners collaborated to develop specific priorities for catalysing a “Big Push Against Malaria.”16

Priorities of the Big Push Against Malaria

- Advance national leadership, accountability, and an integrated malaria response

- Protect funding for malaria and advocate for new resources (including innovative financing)

- Strengthen data systems and enable data-driven decision-making

- Increase accessibility, acceptability & quality of existing interventions

- Develop and prepare for rapid introduction of new fit-for-purpose tools

- Improve coordination between global, regional, and country partners for efficient resource use

2.1. Advance national leadership, accountability, and an integrated malaria response

2.1.1 Regional & Global Leadership

African Union Summit (February)

The Heads of State and Government adopted the African Union Roadmap to 2030 & Beyond: Sustaining the AIDS Response, Ensuring Systems Strengthening and Health Security for the Development of Africa, which builds on existing commitments17 and outlines strategic priorities to sustain and accelerate progress against malaria, HIV, TB, NTDs, Hepatitis and Non-Communicable Diseases. The roadmap highlights the importance of “continental and Member States’ ownership and leadership” with an emphasis on the integration of health services using the “One Stop Shop” concept that builds on the “One Approach, One Plan and One Budget” initiative.18 Central to this is advocacy by leaders in Africa to sustain malaria elimination and health high on the global, continental, regional, and national development agendas.

African Union Roadmap to 2030 & Beyond Objectives

- Enhance healthcare infrastructure and workforce capacity to provide quality services for all through strategic partnerships.

- Ensure that prevention, treatment, and care services are accessible to every individual, particularly marginalized and vulnerable populations.

- Engage communities in health initiatives, promoting awareness, and fostering ownership of health outcomes.

- Promote shared responsibility and global solidarity by developing innovative financing mechanisms and mobilizing both domestic and international resources.

- Integrate health initiatives into broader development goals to create resilient communities capable of addressing current and future health challenges.

Led by President-Advocate Duma Gideon Boko as Chair of ALMA, the Heads of State and Government issued Assembly Decision 904(XXXVIII) recognizing that “ending malaria requires urgent, integrated and innovative solutions that engage the whole of government and whole of society.” They called on Member States to sustain and increase domestic funding for malaria, use development bank resources (e.g., World Bank IDA) and innovative financing, integrate malaria into the broader health agenda, and invest in innovation and new tools to scale up next-generation commodities.19

The ALMA chair launched the “Zero Malaria: Change the Story” campaign. This advocacy initiative—which falls under the umbrella of “Zero Malaria Starts with Me!”—elevates the voices and experiences of children of Africa and how malaria affects them, their educations, their families, and their communities.20

World Health Assembly (May)

On the sidelines of the World Health Assembly Health Ministers from Africa issued a unified call for a “Big Push” to eliminate malaria, committed to enhanced domestic resource mobilisation, called for a successful replenishment of the Global Fund, and urged global partners to increase support—warning that failure to act now could reverse hard-won gains.

- The AU Commission highlighted the AU’s Roadmap as a guiding framework for reducing dependency on external aid and promoting greater ownership and leadership by Member States in financing their national health agendas, including efforts toward malaria elimination.

- ALMA and the RBM Partnership announced the Ministerial Malaria Champions Initiative, which engages and empowers government ministers to champion malaria elimination by mobilising resources, driving cross-border collaboration, and scaling up innovations.

- ALMA, Malaria No More UK and Speak Up Africa also launched the next phase of the Change the Story campaign, highlighting the experiences of children most affected by malaria, with stories from countries including Uganda, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire.

Ministerial Malaria Champions

Angola, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

WHO Regional Committee for Africa (August)

The WHO AFRO Regional Committee adopted a resolution on Addressing Threats and Galvanizing Collective Action to Meet the 2030 Malaria Targets,21 committed to fostering country ownership, strengthening health systems to deliver quality services, retaining health workers, improving supply chains, using data analytics to target interventions, and increasing domestic funding.

The Ministerial Champions unveiled the Champions’ Accountability Scorecard, which provides a common tool to track progress, share best practices, and hold leaders accountable.

Nigeria Big Push (September)

The “Harnessing Africa’s Central Role in the Big Push Against Malaria” meeting held in Abuja, Nigeria in September 2025 convened ministers, parliamentarians, civil society, private sector leaders and experts to advocate for translating political momentum into Africa-led operational plans based on the Nigeria example. The meeting affirmed that Africa is prepared to own, finance and lead the global effort to eliminate malaria.

- Nigeria highlighted its new national and multisectoral operational plan to eliminate malaria, demonstrating decisive national ownership (e.g., expanding integrated ITN/SMC campaigns, scaling up local production of diagnostics and nets, multisectoral End Malaria Councils).

- Other stakeholders from across the continent underscored the importance of shared leadership (e.g., Ghana’s legislated malaria budget line, Cameroon’s financing diversification and micro-stratification, and Cabo Verde’s post-elimination vigilance).

- Participants pledged to treat malaria as a national development priority by creating ring-fenced budget lines, legislating health-focused levies (e.g., on telecoms, tobacco and alcohol), accelerating rollout of new commodities and interventions, and increased multisectoral and integrated approaches.

UN General Assembly (September)

At a high‑level event during the 78th UN General Assembly (UNGA), Heads of State and Government from Africa described how shrinking aid budgets threaten malaria programmes and called for a renewed commitment to global health security. Collectively they recognised that between 2021 and 2025 alone, ODA for health in Africa declined by an estimated 70%,22 even as widening equity gaps, humanitarian crises, and displacement have expanded both needs and vulnerability. They also called on global partners to fully replenish the Global Fund, renew the World Bank’s Malaria Booster Programme, and support a public-private health accelerator to mobilise domestic resources. The future of Africa’s health financing, they noted, must be in “Africa’s hands” and highlighted the establishment of End Malaria Councils and Funds to drive local ownership.23

The fight against malaria is becoming increasingly complex. Shrinking budgets, rising biological resistance, humanitarian crises, and the impact of climate change are all contributing towards creating a perfect storm of challenges.

President Advocate Duma Gideon Boko – Republic of Botswana and Chair of ALMA

Essential programmes to eliminate malaria have been compromised. This leaves millions without care and erodes decades of progress that has been made so far.

H.E. Cyril Ramaphosa – President of the Republic of South Africa, Chair of the 2025 G20 Summit and Chair of the Global Leaders Network for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health

Malaria in particular must be eliminated from Africa. Kenya remains committed to the African Leaders Malaria Alliance and the Zero Malaria Starts with Me Campaign. Through our malaria youth corps, we are mobilizing them and communities to lead this fight.

H.E. William Ruto – President of the Republic of Kenya

2.1.2 Regional Economic Communities

The Regional Economic Communities (RECs) continue to take a leading role in the malaria-elimination agenda. Each REC has put forward a regional plan and adopted a scorecard tool to drive accountability and action. Performance against these commitments is reviewed during summits of Heads of State and Government as well as ministerial meetings.

The RECs are working amongst their members and increasingly across regions to build capacities, share best practices, harmonise policies, and enhance data sharing for monitoring of drug resistance, registration of new commodities, promotion of local manufacturing, climate change modeling, and responses to conflict and humanitarian crises.

The RECs are also evaluating opportunities to support resource mobilisation (e.g., IGAD has established a funding mechanism to address climate change and health), especially for pooled procurement.

2.1.3 Country Leadership

Country ownership and leadership are critical to accelerating progress against malaria. The “Big Push”, “Accra Reset” and other political declarations and decisions made during 2025 recognise the importance of malaria-endemic countries leading the fight against malaria and aligning donor resources and partner support to national priorities and strategies.

Zero Malaria Starts with Me

Launched in 2017, the Zero Malaria Starts with Me! campaign has been the official continent-wide initiative to end malaria. This campaign has three high-level objectives: advocate for malaria to remain high on the development agenda, mobilise additional domestic resources, and engage and empower communities to take action. The campaign has been launched in more than 30 Member States.

During 2025, ALMA, MNMUK and Speak Up Africa supported the “Zero Malaria: Change the Story” initiative. This campaign elevates the stories of children from across Africa to highlight how malaria affects them, their families, and their communities.

Public Sector

Government ministries and parliamentarians play a pivotal role in the fight against malaria through the provision of resources, technical expertise, and sustained advocacy within their respective sectors. Ministries (e.g., finance, education, women & children, information, mining, energy, tourism) can mobilise support for malaria programming and facilitate the integration of malaria-related priorities into broader national development agendas. Their engagement ensures that malaria remains firmly embedded as a cross-sectoral priority, thereby enabling the more effective implementation of national malaria strategic plans and safeguarding long-term progress against the disease. Likewise, legislators shape policy, secure budgetary allocations, and enact legislation that enables malaria control and elimination. As community and constituent representatives, they also engage in advocacy at all levels (including on the international stage) to raise awareness of malaria’s impact and coordinate stakeholder action.

The RBM Partnership, Ghana, Impact Santé Afrique, and other partners launched the Coalition of Parliamentarians Engaged to End Malaria in Africa (COPEMA) in 2025 to strengthen collaboration between policymakers and NMCPs and equip parliamentarians with the tools necessary to advocate for malaria control and elimination.

Office of the President / Vice President

- Tanzania: Led the development of a multisectoral collaboration framework that includes all sectors. Permanent secretaries of each ministry identify and implement malaria-smart activities.

Agriculture / Fishing

- Equatorial Guinea: Collaborating on use of insecticide to assess the impact on resistance and strengthen coordination to reduce risk of insecticide resistance.

- Madagascar: Supported the design and distribution of tools and messages to avoid use of ITNs for fishing.

Defence

- Senegal: Provided logistics (e.g., transportation, logistics, distribution) for the national ITN campaign.

Education

- Burkina Faso: Serves as a channel for raising awareness and training students on malaria prevention, including through age-appropriate lessons and curricula.

- Senegal: Supports dissemination of social and behaviour change communications.

Environment

- Kenya: Established a technical working group to assess the impact of climate on malaria.

Finance

- Botswana: Engaged to include malaria in national development plans and on the structure for the Malaria & NTDs Elimination Council, whose members include other ministries.

- Ethiopia: Allocated $22 million for malaria in the national budget after a reduction in donor funding.

- Ghana: Under the direction of the President, increased funding for malaria to close budget gaps and working to establish a domestic fund.

Labour

- Sudan: Led the development of a community-based strategy to deploy CHWs to support malaria case management and other primary health care services.

Local Government

- Botswana: Partnered as trusted and critical implementers of malaria interventions and messaging at the community level.

- Burkina Faso: Improve sanitation and undertake other activities at the community level to prevent mosquito breeding sites.

- Kenya: Engaged village elders as trusted messengers and community mobilisers during the mass net campaign.

Parliamentarians

- Senegal: The NMCP organized a meeting with parliamentarians to advocate for increased national resources for malaria and for the creation of a parliamentary caucus.

- Nigeria: Members of the National Assembly held a workshop on the challenges facing the country with malaria. Following a presentation by the NMEP and the Nigeria End Malaria Council, the members pledged to sustain the malaria line item in the national budget, to use the national malaria scorecard for advocacy, and deploy $2 million in constituency funds.

Private Sector

The private sector plays a critical role in the fight against malaria by providing financial and in-kind resources, driving innovation, and leveraging its expertise to support malaria programmes. Companies contribute through in-kind support, direct investment, and corporate social responsibility funding, as well as by providing technical expertise and logistical assistance to national malaria programmes. The private sector can contribute significantly to innovation and to boosting the capabilities of malaria programmes—particularly in areas such as supply chain and logistics management, advertising and communications campaigns, data and technology and community engagement—thereby enhancing efficiency and strengthening public-private partnerships. As part of efforts to mobilise resources, Member States are establishing forums (e.g., End Malaria Councils, Angola’s CATOCA) that bring together private sector leaders, as well as other national leaders, to coordinate multisectoral advocacy, action and resources.

Extractives

- Tanzania: The mining collectively sector pledged to work with the government and allocate funding to support for malaria interventions in areas where they operate.

- Zambia: First Quantum Minerals and the End Malaria Council mobilised resources to support the procurement of bicycles and other resources for CHWs.

Manufacturing

- Kenya: SC Johnson is supporting the revitalisation of community health centres and communications.

Telecom & Media

- Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal: CANAL+ provides in-kind messaging support for SBCC

- Burkina Faso: Orange provided free data to synchronize and track ITN and SMC campaigns.

Civil Society & Communities

Engaging and empowering communities is a key priority under the Catalytic Framework, Big Push, Zero Malaria Starts with Me and other malaria initiatives and decisions. Civil society organisations (CSOs), religious leaders, and youth each have important roles in reaching vulnerable populations and leading advocacy to ensure that ending malaria is a priority at all levels of society.

Civil society organisations (CSOs) amplify the voices of the community and are instrumental in leading advocacy, promoting accountability, and advocating for those disproportionately affected by the disease—women, children, living in rural communities. CSOs raise awareness about the dangers of malaria, advocate for policy changes, and advocate for increased funding to support malaria interventions. In rural areas, where access to healthcare is often limited, CSOs help bridge the gap by promoting the use of insecticide-treated nets, access to antimalarial medicines, and improved healthcare infrastructure. They also engage in education campaigns to empower women—who are often the primary caregivers—on how to protect themselves and their families from malaria and amplify their concerns to leaders at all levels.

- Nigeria: The Federation of Muslim Women Associations of Nigeria (FOMWAN) and National Council of Women Societies (NCWS), both members of the End Malaria Council, supported mass media and targeted messaging encouraging women to seek testing and treatment for malaria.

- Tanzania: Rotarians coordinated awareness campaigns, volunteer mobilization, school programmes, and mapping of ongoing & planned malaria activities.

Religious leaders leverage their influence and trusted status within communities to promote malaria prevention and treatment. Through sermons, community gatherings, and faith-based networks, they raise awareness of the importance of using mosquito nets, seeking timely diagnosis, and adhering to treatment protocols. Religious leaders also serve as advocates, engaging policymakers and mobilising community-level action. Their authority helps to reduce stigma, encourage healthy behaviours, and support national malaria campaigns, making them key partners in the drive to eliminate malaria.

- Tanzania: A coalition of religious leaders launched an inter-faith campaign to sustain the visibility of malaria and mobilise resources. The Archbishop of the Catholic Church coordinated faith leaders, private sector partners, and regional and district authorities to mobilize larvicide and promote SBCC messages in congregations.

- Zambia: Faith Leaders Advocating for Malaria Elimination (FLAME) convened religious leaders and organisations from five countries in Livingstone to share best practices for supporting the fight against malaria (especially cross-border).

Member States are increasingly engaging young people in the fight against malaria, NTDs and in advancing Universal Health Coverage through national Malaria and NTDs Youth Corps. These coalitions of youth leaders mobilise communities, lead advocacy and communications campaigns, and work hand-in-hand with national malaria and NTD programmes. Malaria Youth Corps are involved in key activities with NMCPs including distribution of ITNs, IRS, SMC, use of scorecard accountability and action tools, and community mobilisation. To date, 45 Member States have recruited malaria youth champions, 19 have launched Malaria Youth Corps, and more than 3,000 youth leaders are engaged in the fight against malaria.

- Zambia, Uganda, Mozambique, Eswatini, Nigeria, and DRC: Supported the deployment of community scorecards and gender-responsive dialogues and initiatives.

- Liberia: Contributed to the preparation and implementation of a national marathon to promote malaria vaccine uptake.

- Nigeria: A high-level meeting was held between the Youth Corps and the Commissioner for Health and Permanent Secretary to advocate about youth engagement in the fight against malaria and NTDs.

2.2 Protect funding for malaria and advocate for new resources (including innovative financing)

2.2.1 Global Resource Mobilisation

Eighth Replenishment of the Global Fund

In November, 29 countries, including 8 Member States, and 12 private organisations made initial pledges totaling $11.3 billion towards the Eighth Replenishment of the Global Fund (2027-2029).24 While additional pledges are expected to be made through February 2026, this total is significantly less than the Replenishment’s $18 billion target and a reduction compared to the Seventh Replenishment (2024-2026).

GAVI Replenishment

Gavi, the Global Vaccine Alliance, concluded its latest replenishment with $9 billion pledged to support vaccination for 2026-2030, short of its $11.9 billion target. Gavi financing is instrumental in supporting the rollout of vaccines across Member States.

World Bank IDA Replenishment

The decision from the 2024 AU Summit on malaria called for Member States to work with the World Bank to incorporate malaria into IDA financing. Africa receives the bulk of IDA financing ($22 billion, 71% of total in FY2024). The December 2024 IDA21 replenishment secured $100 billion in financing. Incorporating malaria into IDA would provide critical resources for closing program gaps; deploying next-generation tools; strengthening community health worker programmes; reinforcing data and supply chains; and building climate-resilient health systems—integrated within primary and universal health care.

World Bank Malaria Booster

Throughout 2025, leaders from Africa called for a renewal of the World Bank Malaria Booster programme—building on the success of the first programme at catalysing rapid deployment of new interventions and rapid progress against malaria. On the sidelines of the UNGA, President Advocate Duma Gideon Boko urged the Bank to channel resources toward a new malaria booster window, recalling the World Bank’s 2005 Malaria Booster Program which helped countries to significantly accelerate progress towards achieving the malaria MDG targets.

2.2.2 Regional Economic Communities

The RECs are exploring opportunities to establish financing mechanisms to support pooled procurement and cross-border coordination of malaria interventions.

2.2.3 Domestic Resource Mobilisation

Member States are taking bold steps to boost domestic funding for malaria, recognizing that greater self-reliance is crucial to sustain progress amid flatlining donor support. Ministers have highlighted the urgency of closing Africa’s malaria funding gap and securing additional resources for resilient health systems. Governments are increasing national health budgets, enacting policies for dedicated malaria financing, and partnering with the private sector to mobilize new resources. Countries negotiating bi-lateral compacts with the US have also made co-financing commitments. Finally, countries are launching national End Malaria & NTDs Councils (see above) to mobilise commitments across all sectors of society.

- Benin: Raised its national malaria budget by 28.5% for 2025, building on a 140% increase in funding from 2022 to 2023.

- Burkina Faso: Maintained health expenditure above 13% of the national budget and allocated an extra 5 billion CFA francs to expand malaria vaccine rollout and 2.7 billion CFA for other interventions.

- Nigeria: Approved an additional US$200 million for the health budget to offset the shortfall created by the suspension of US PMI funding. Nigerian legislators also committed to ending over-reliance on donors by committing $2 million in constituent funds towards malaria activities and increasing public funding for national and state-level malaria programs.

- Senegal: Allocated 330 million CFA to purchase SP for IPTp and committed to increase government funding to purchase commodities.

- Sudan: Increased funding for malaria by 400% in 2025 with plans to further expand funding in 2026.

End Malaria Councils & Funds: A Tool for Multisectoral Advocacy, Action & Resource Mobilisation

The Heads of State and Government of Africa have called upon Member States to accelerate the establishment of national End Malaria & NTDs Councils (EMCs).25 EMCs are country-owned and country-led forums for coordinating multisectoral advocacy, action and resource mobilization (see Domestic Financing below) in partnership the NMCP. Council’s members are senior leaders drawn from government (e.g., ministers, parliamentarians), the private sector (e.g., CEOs), civil society (e.g., religious leaders, women’s societies, youth). 12 Member States have launched EMCs, including Burkina Faso, Liberia, and Sudan in 2025.

End Malaria Councils play a critical role in addressing operational bottlenecks and resource gaps by leveraging their influence, networks, and expertise to mobilise commitments from across all sectors. The members work with the Ministry of Health to identify addressable gaps under the national strategic plans; advocate for ending malaria to be a top strategic priority; and mobilise their sectors’, industries’, and communities’ unique expertise, assets, and resources to help achieve national targets. Mobilised commitments continue to strengthen malaria interventions (including their scaling up), address persistent funding shortfalls, and increase the visibility of malaria through nationwide and community-level communication campaigns. Furthermore, several EMCs have initiated innovative measures to promote local manufacturing of malaria commodities, thereby advancing sustainability and resilience in the fight against the disease. To date, EMCs have mobilised more than $186 million in commitments across all sectors, including more than $106 million in Q4 2024-Q3 2025.

Illustrative Commitments from 2025

- Eswatini: Launched a nationwide resource mobilisation campaign with leadership by the Minister of Finance and private sector.

- Nigeria: Secured a commitment to include $63 million in the national budget, up to $12 million for constituent resources, and established a financing mechanism for pooling private sector resources.

- Tanzania: SC Johnson contributed resources for capacity building for biolaviciding at the district-level, Tanzania Bankers Association donated advertising, professional services, and an initial pledge of 11 billion TZS to the End Malaria Trust.

- Zambia: Secured $11 million for the procurement of ITNs and sustained national resource mobilisation and buy-a-bicycle campaign for CHWs.

2.3 Strengthen data systems and enable data-driven decision-making

Member States are focused on enhancing the use of health data and information systems to guide decision-making and improve the efficiency of interventions. This includes using real-time data to drive action. The continued adoption of digital tools that facilitate more real-time reporting and integration of novel data sources enables Member States to proactively track and confront the threats posed by the perfect storm.

2.3.1 Strengthening of Health Management Information Systems and National Malaria Data Repositories

The big push to accelerate malaria elimination will require more sophisticated use of data for action, harnessing new and existing technologies such as artificial intelligence and making better use of climate data. Leveraging emerging technologies and building capacity for use of local data strengthens data quality and availability and also enables quicker, more effective responses to malaria upsurges. Member States have accelerated efforts to strengthen their health management information systems (HMIS)—the most common being DHIS2—and establish national malaria data repositories (NDMR) to unify fragmented datasets from routine surveillance, campaigns, logistics, and other sources.

The RECs are also supporting regional collaboration and proactive identification of new data sources to support early warning systems and Member State planning. For example, the IGAD Climate Prediction & Applications Centre is supporting regional climate-health modelling, early warning systems related to climate change, and adaptation measures. The RECs are also working with their members to increase cross-border data sharing and interoperability to enable better coordination (e.g., cross-border vector control campaigns).

National Malaria Data Repositories

- DRC: Implemented the National Malaria Control and Development Repository (NMDR) system, facilitating access to the information and data required for decision-making and the refinement of the national malaria control policy.

- Ethiopia: Selected by IGAD as the best data repository. Government invested significantly in digitalization and the Prime Minister launched a digital strategy and health platform in 2025.

- Niger: The National Malaria Control Programme launched an NMDR mid-2025 to pool all malaria-related data into a single portal, allowing programme managers and partners to access one source for timely malaria data, greatly improving analysis and decision-making.

Health Management Information Systems

- Guinea & Togo: Integrated a DHIS2-based NMDR into their national HMIS, collaborating on common roadmaps to roll out these platforms.

- Kenya: Laws ensure that all health data is integrated into a “digital super highway” that provides access for all health workers. The NMCP is integrating the digital platform used for ITN distribution onto the central HMIS platform, which will reduce the burden of registering households.

- Madagascar: Using DHIS2 for rapid decision-making, especially the scorecard on the resurgence of malaria. Integrating weekly and monthly data reporting for routine services down to the health facility.

- Rwanda: Integrating data platforms and moving from monthly to weekly reporting—including cases reported from health facilities, communities, climate data, intervention data, surveillance data.

- Senegal: DHIS2 is used to monitor routine interventions and case investigations. Also using the case tracking feature to monitor transmission. All districts that are using SMC and MDA are digitalized.

- Sudan: Used data from DHIS2 to tailor malaria interventions (e.g., ITN campaign, IRS) for the most vulnerable populations.

- Uganda: Integrated climate data into its HMIS and scorecard management tools, improving capacity to predict and mitigate malaria upsurges.

2.3.2 Scorecard Management Tools

Across Africa, the growing use of health scorecard tools signals a collective push for openness, accountability, and smarter spending to improve results. As Regional Economic Communities and Member States refine and institutionalize these tools, they equip citizens, officials, and health workers to play a more active role in building stronger, more resilient health systems.

ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action

The ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action is the primary, evidence-based tool for driving relevant, high-level commitments amongst the Heads of State and Ministers across Africa. Issued quarterly, it tracks priority indicators for every Member State—including malaria, maternal and child health, and neglected tropical diseases—and pairs them with practical follow-up recommendations. The scorecard is shared with Heads of State and Government, AU Ambassadors, and Ministers of Health, Finance, and Foreign Affairs to spur timely action.

In 2025, indicators related to domestic resource commitments, rollout of the malaria vaccine, and NTD budget lines were added to the ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action.

Country Scorecard Management Tools

National and subnational scorecard tools remain important country-owned, evidence-based mechanisms for driving accountability and action for the fight against malaria. These tools highlight performance against key indicators tied to national malaria strategies. They provide a simple and accessible mechanism for leaders at all levels to identify operational bottlenecks and resource gaps. Scorecard tools also increasingly include multi-sectoral data, enabling cross-cutting actions beyond the health sector. For example, several Member States have incorporated data on the environment and gender to inform more effective and equitable malaria strategies.

In 2025, Member States and their partners allocated over $54 million to address areas of underperformance identified through scorecard tools, representing just a snapshot of the resources mobilised. Member States and their partners also contributed over US$6 million to support scorecard implementation in 2025.

Scorecards tools at all levels (community, national, regional, and continental) have become entrenched as key instruments of accountability and action, driving a more responsive and inclusive malaria and health fight in Africa. End Malaria Councils, youth networks, civil society, parliamentarians and legislators use scorecards as evidence-based tools to advocate for policy and budget shifts, mobilise funds and in-kind support, and organise campaigns at the community-level.

The expansion and decentralization of scorecard tools strengthen accountability at every level by making performance visible and actionable. 22 Member States are sharing their scorecards publicly on the ALMA Scorecard Hub and in other multisectoral and community-level forums. By making health data accessible and actionable to broad audiences, the scorecard tools in 2025 are helping transform data into concrete interventions—from communities identifying and addressing gender barriers to accessing malaria and health services, to a Head of State and Government launching a remedial action after scorecards revealed low insecticide-treated net coverage. Crucially, the widespread training and decentralization of scorecard tools continued throughout 2025. Since 2021, more than 3,000 people—from community leaders and health workers to parliamentarians—have been trained to use national and subnational scorecards to track trends and trigger timely action. With more districts and facilities using digital dashboards, routine data are consolidated and visualized in ways that support real-time decisions, tighter supervision, and targeted resource allocation.

- Malawi: The Malaria Scorecard identified low ANC/postnatal ITN coverage (65%). Intervention in Q1 2025 (e.g., task-shifting, documentation, client-centred scheduling) increased coverage to 98%.

- Zambia: Targeted redistribution increased ANC ITN distribution coverage from 87% to 100% in Q1 2025 after the scorecard flagged stock imbalances affecting coverage.

- Burkina Faso: Trained multisectoral stakeholders and leadership from the national down to the health facility level on the use of scorecards (malaria and nutrition).

- Ghana: Integrated the scorecard into pre-service training to ensure health workers at all levels are familiar with its uses.

- Nigeria: Developed a Sector-Wide Approach (SWAp) scorecard (integrated across programmes, including malaria) to track national and state priorities. This scorecard closely aligns with the revised strategic priorities announced by the Ministry and enables monitoring of key health priorities across programmes. This scorecard also enables the inclusion of State-specific indicators in subnational scorecards.

- Kenya: National rollout of the malaria scorecard and surveillance tools across all 47 counties (including sub-counties) supported by $190,000 mobilised (Global Fund) to conduct the rollout. The scorecard in Bungoma County supported budget advocacy, resulting in KES 424 million ($3.3 million) mobilised for service-delivery gaps (ambulances, MPDSR meetings, blood services).

- The Gambia: Following the rollout of the NTD scorecard, NTDs were included in the country’s Recovery Focused National Development Plan signed by the President. The plan commits to reducing schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis prevalence by 75% by 2027. Advocacy and training with parliamentarians led to the government allocating $200,000 for NTD medicines in 2025 and committing to establish a dedicated NTD budget line to ensure sustained domestic funding.

2.3.3 Subnational Stratification and Tailoring

Member States are implementing subnational stratification and are defining the most impactful packages of interventions tailored to sub-national burden estimates and level of available resources. Optimisation, especially when resources are insufficient, supports countries to maximise impact with the available resources. Using granular data (e.g., district-level incidence, prevalence, and receptivity factors), health ministries updated malaria stratification maps to guide resource allocation. This data-informed tailoring ensures that, especially amid funding constraints, the most effective mix of tools (e.g., nets, indoor spraying, chemoprevention) is deployed in the right places. It also means low-burden zones can transition to elimination strategies while high-transmission areas receive strengthened control measures. This process helps optimize insufficient resources to maximise impact. Additionally, low-burden zones can transition to elimination strategies while high-transmission areas receive strengthened control measures.

- Angola: Undertaking mathematical modeling to determine where to distribute next-generation ITNs.

- Burkina Faso: Targeting interventions through subnational stratification in the 2026-2030 strategy, including data on insecticide resistance and partial drug resistance.

- Cameroon: Adopted micro-stratification to refine malaria risk mapping. This approach, coupled with diversified financing strategies, allows Cameroon to target interventions at the sub-district level. Early results indicate more efficient use of commodities by concentrating them where incidence is highest.

- Guinea: Used subnational tailoring to update its 2024-2026 malaria operational plan, engaging local stakeholders in analysing district data and prioritizing interventions accordingly.

- Madagascar: Stratification goes down to the district level and exploring increasing stratification down to the health facility level. Combining this with surveillance data (e.g., insecticide resistance detected in 10 districts) supported planning and distribution of next-generation commodities.

- Rwanda: Subnational stratification is guiding the implementation of interventions (e.g., ITNs, IRS, reactive case detection, response to outbreak) and the introduction of MFT and selection of insecticides based on resistance surveillance data.

- Senegal: Established a technical working group to support subnational stratification (e.g., identification of hotspots), which classified the country into different epidemiological zones and planned interventions for each zone.

ALMA’s Scorecard Web Platform was updated in 2025 to support easier subnational stratification. Malaria scorecard tools are being enhanced to help countries monitor the progress and effectiveness of their targeted intervention packages.

- Mozambique, Uganda: Employing district scorecard reviews alongside the stratified plans to ensure accountability for delivering the promised interventions in each stratum.

- Tanzania: Uses the scorecard to monitor the implementation of tailored intervention packages across regions, resulting in increased impact and efficient use of resources.

2.4. Increase accessibility, acceptability & quality of existing interventions

Member States have the most advanced toolkit ever for combatting malaria. The current tools include a number of cost-effective interventions (e.g. rapid diagnostic tests, ACTs, ITNs, IRS, SMC/PMC, malaria vaccines). Over the past 20 years, these tools have contributed to the significant drop in the numbers of severe malaria cases (1.6 billion cases avoided) and deaths (12.4 million deaths avoided). Nevertheless, biological resistance, insufficient financing, climate change, pandemics, conflict and humanitarian crises undermine the efficacy, coverage, and access to these life-saving tools. This “perfect storm” increases the imperative for sustaining and scaling up existing, proven interventions—as well as ensuring equitable and affordable access to these tools (e.g., through market-shaping) to mitigate upsurges.

2.4.1 Vector Control

Countries are rapidly introducing next-generation insecticides and ITNs. The WHO revised its guidance on IRS to include chlorfenapyr as a recommended insecticide. Strong country leadership has driven a rapid shift to chlorfenapyr dual active ingredient nets with dual-AI nets accounting for 74% of nets distributed in 2025. These new nets, which incorporate two different classes of insecticides to ensure that mosquitoes resistant to one are still targeted by the other, are 55% more effective than pyrethroid-only nets.26

Several Member States have also been testing new approaches for implementing larval source management, such as by drone (e.g., Rwanda, Kenya, Djibouti, Senegal, Madagascar).

2.4.2 Case Management

Effective malaria case management requires quick access to diagnostics (e.g., RDTs) and antimalarial treatments (e.g., ACTs). ACTs remain the recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria caused by the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. Partial resistance to artemisinin, linked to mutations in the malaria parasite, has recently emerged in several countries in Africa, leading to slower parasite clearance times. The WHO launched a strategy to respond to drug resistance in Africa in 2022 including the use of multiple first-line therapies to extend the therapeutic lifespan of ACTs.27 Member States are also undertaking activities to expand the availability of interventions (and implementing multiple first-line therapy strategies to address partial drug resistance (e.g., Rwanda developed an MFT strategy).

2.4.3 Malaria Vaccines

With support from Gavi and other donors, 24 Member States have introduced or begun rolling out the two approved malaria vaccines for children under the age of 5. Burundi, Uganda, Mali, Guinea, Togo, Ethiopia, Zambia and Guinea-Bissau introduced the vaccine for the first time in 2025. Additionally, The Gambia and Guinea-Bissau’s applications to introduce the vaccine have been approved.28

2.4.4 Local Manufacturing

Member States are expanding local manufacturing of malaria and other health commodities. Local manufacturing stimulates economic and industrial development through job creation and stimulate research and innovation on the continent. It also helps minimise supply-chain shocks (as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic) and supports broader objectives related to regional and continental trade integration.

Recognising the need to reduce Africa’s dependence on imports (currently 99% of vaccines & 95% of medicines are imported, the AU, RECs, and Member States are strengthening the prospects for local manufacturing and vaccine development through regulatory harmonisation, technology transfer, and market shaping. The AU, Africa CDC, ALMA, and Member States (e.g., Nigeria, Tanzania, Angola) are actively negotiating with a number of multinational manufacturers to transfer the technology and capacity to manufacture various malaria commodities in Africa.

- Nigeria: Entered into a partnership with two manufacturers for ACTs and two manufacturers for RDTs and is working to have local manufacture of next generation ITNs.

- Tanzania: Progressing with the formal certification of Kibaha Biolarvacide, which could be rolled out to support vector control in other countries.

- Zambia: The Zambia End Malaria Council also initiated small-scale production of ITNs during 2025.

2.4.5 Cost Mitigation & Market Shaping

To mitigate the increasing cost of malaria commodities, Member States continue to pursue pooled procurement in partnership with the Global Fund, Africa CDC and the RECs. Pooled procurement enables countries to gain a scale advantage when negotiating the prices for commodities. Of particular note, Nigeria, which has devolved the fight against malaria largely to the state-level, is implementing a national affordable diagnostics medicines facility to support pooled procurement across states.

2.5 Develop and prepare for rapid introduction of new fit-for-purpose tools

Sustaining investment in R&D and preparing for the rapid introduction of innovative tools is essential to accelerating progress and staying ahead of biological resistance. There has also been renewed interest in 2025 with several Member States making significant progress towards large-scale production of malaria commodities in Africa.

2.5.1 Malaria Commodity Pipeline

Currently there are approximately 150 malaria interventions in development that have the potential to complement existing tools and address resistance. With support from the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD), RECs, WHO, and other partners, Member States are fostering environments for research and the development of regulatory frameworks to advance emerging technologies and enhance malaria control efforts. As new products become available, Member States are encouraged to evaluate each based on WHO guidance and by assessing the impact of the interventions relative to, or in combination with, existing tools and based on the availability of sufficient resources.

Malaria Vaccines

Two mRNA recently vaccines entered the pipeline with one of them already in clinical trials. Applying the same principles that developed COVID-19 vaccines, mRNA technology could potentially develop vaccines targeting multiple malaria parasite stages enhancing impact.

Antimalarial Medicines

There are 48 antimalarial medicines in development, including promising approaches involving novel, non-artemisinin combination therapies. Several drugs are in late-stage development, including through the partnerships between MMV and GSK, Merck, and Novartis. Many of these new antimalarial candidates are expected to become available for treating uncomplicated and severe malaria within the next decade. The availability of these new drugs could significantly enhance treatment and mitigate resistance.

Vector Control Products

In 2025, WHO prequalified the use of two spatial repellents products produced by SC Johnson for malaria prevention and control in areas where there is ongoing malaria transmission. Spatial repellents, which are the first new vector control intervention introduced in decades, emit active ingredients into the air to kill mosquitoes, deter them from entering treated spaces, and prevent them from locating and biting human hosts. Official WHO guidance recommends that spatial repellents be used alongside ITNs and IRS as a supplemental method of vector control.

Research is continuing on the innovative gene-drive approach, including confined field trials. Gene-drive strategies aim to decrease mosquito populations by reducing female mosquito numbers or genetically modifying Anopheles mosquitoes so that they cannot transmit the malaria parasites to humans. Support for testing the safety and impact of this new technology is critical before considering their large-scale use. Additionally, the introduction of gene-drive technologies presents inter-ministerial and multisectoral considerations requiring input from the Ministry of Environment, food and drug regulators, and communities.

Diagnostics

There are 29 novel diagnostics in development. Half of the products under development focus on addressing mutations (HRP2) to the malaria parasite and for detecting asymptomatic patients, which are critical for regions approaching elimination.

2.5.2 Regulatory Strengthening

African Medicines Agency

The African Medicines Agency (AMA) was established with the goal of harmonizing and strengthening the regulation of medicines and medical products across Africa. As the second specialized health agency of the African Union, AMA aims to improve access to safe, effective, and high-quality medicines by supporting local pharmaceutical production, coordinating joint assessments of medicines, and promoting information sharing among national and regional regulatory authorities. With 31 countries having ratified the AMA Treaty—are more on track to ratify—the AMA continues to make progress towards operationalisation.

Reliance-based Regulatory Approach

The RECs are undertaking activities to streamline and harmonise the regulatory environment for the introduction of new commodities. Each REC is working with its members to implement reliance-based approach that would enable mutual recognition of regulatory approvals for malaria commodities. The RECs are also considering opportunities for reliance/recognition between RECs, which would accelerate the approval and registration of new commodities across the continent.

Progress Against Neglected Tropical Diseases

Countries eliminating NTDs in 2025

In 2025, five African countries were validated for elimination of some NTDs as a public health problem.

- Guinea was certified for eliminating the gambiense form of human African trypanosomiasis as a public health problem

- Niger became the first country in the African Region to eliminate onchocerciasis

- Burundi, Mauritania and Senegal were certified for eliminating trachoma as a public health problem

- Kenya was certified for eliminating the rhodesiense form of human African

Impact of Declining Funding

To mitigate the effects of USAID cuts on NTD activities, countries were encouraged to identify existing opportunities to integrate NTD interventions such MDAs in the existing campaigns. Countries including Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Niger and Rwanda organized MDAs integrated with existing campaigns (e.g., health weeks, polio campaigns, malaria campaigns).

ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action

The ALMA scorecard is now tracking four NTD related indicators. In addition, ALMA supported the AUC to encourage countries to submit additional NTD data on the implementation of the Continental Framework for NTDs. For example, the percentage of countries that submitted data on the ‘Existence of a budget line for NTDs’ increased from 51% in 2024 to 71% in 2025 with 22 countries now report having a standalone NTD budget line.

NTD Indicators

- Mass Treatment Coverage for Neglected Tropical Diseases

- Percentage of Mass Drug Administration achieving WHO Targets

- Government Vector-Borne Diseases included in Nationally Determined Contribution

- Budget allocated for NTDs

National NTDs Scorecards

Twenty-two Member States have developed national NTDs Scorecards and in 2025, ALMA supported targeted countries to revise and update their scorecards and or to decentralize their NTD scorecards to at least regional level. Use of these scorecard tools has enhanced NTD data reporting with countries,29 increasing the number of NTD indicators in national Health Management Information Systems (e.g., DHIS2). Over 75% of NTD Master Plans are reported into DHIS2. 15 Member States30 also increased domestic resources for NTDs and mobilized more resources from partners to improve gaps identified during the scorecard analysis.

- Burundi: Conducted NTD scorecard indicator review and adjusted the thresholds based on 2025 targets and the exercise led the country to add more six NTD indicators into DHIS2. The country also reviewed a five -year draft strategy of onchocerciasis and other NTDs elimination in Burundi with new strategy of integration, which led to organize integrated MDA for all targeted Preventive Chemotherapy NTDs.

- Burkina Faso: Scorecard analysis revealed low coverages of hydrocele surgery in Boucle du Mouhoun region and national supervisors were assigned in the region, to supervise the interventions while working with the local teams to mobilize the community members. This improved the hydrocele surgery rate from 14.49% in semester one 2024 to 38.54% in semester two 2024 and to 91.10% in semester one 2025.

- Congo: The NTD scorecard led the country to establish NTD budget line for NTDs and the government contribution to NTDs doubled from 2023 to 2025.

- Gambia: Following the training of members of Gambia National Assembly on the use of scorecard for advocacy, accountability and action, Members of Parliaments voted a budget of 200,000 USD to buy NTD medicines. The country also worked to integrate NTDs into the primary health care package.

- Rwanda: The scorecard analysis led to detect increased cases of schistosomiasis in Gatsibo and Ruhango districts and these districts have been the focus on community mobilization including engaging youth in community awareness activities. The country also elaborated and published a community awareness book on schistosomiasis.

Youth Engagement

In addition, ALMA worked with countries with malaria youth corps to integrate NTDs in their package. Senegal launched Malaria-NTD Youth Corps, Cameroon, Guinea and Malawi Youth Corps revised their legal status to integrate NTDs. Botswana, Rwanda and Togo are also launching these integrated youth corps.

Acknowledgements

This report has been prepared by the African Union Commission, African Leaders Malaria Alliance and RBM Partnership to End Malaria. The drafting and revisions of this report include contributions from national malaria control programmes, development partners, and other stakeholders from across the continent and the global community.

Special Thanks: Jose Martins (Angola), Lisani Ntoni (Botswana), Aissata Barry (Burkina Faso), Antoine Méa Tanoh (Côte d’Ivoire), Samatar Kayad Guelleh (Djibouti), Baudouin Matela (DRC), Matilde Riloha Rivas (Equatorial Guinea), Gudissa Bayissa (Ethiopia), Hilarius Asiwome Kosi Abiwu (Ghana), Kibor Keitany (Kenya), Tiana Harimisa Randrianavalona (Madagascar), Nnenna Ogbulafor (Nigeria), Emmanuel Hakizimana (Rwanda), Aliou Thiongane (Senegal), Ibrahim Diallo (Senegal), Abdul M. Falama (Sierra Leone), Ahmed Abdulgadir Noureddin (Sudan), Anthony Galishi (Tanzania – Mainland), Maulid Issa Kassim (Tanzania – Zanzibar), Inas Mubarak Yahia Abbas (AU Commission), Marie-Claude Nduwayo (AU Commission), Eric Junior Wagobera (AU Commission), Christopher Okonji (AUDA-NEPAD), Afework Kassa (IGAD), Julius Simon Otim (EAC), Ghasem Zamani (WHO EMRO), Vonai Chimhamhiwa-Teveredzi (RBM Partnership), Collins Sayang (RBM Partnership), Melanie Renshaw (ALMA), Stephen Rooke (ALMA), Samson Katikiti (ALMA), Robert Ndieka (ALMA), Foluke Olusegun (ALMA), Abraham Mnzava (ALMA), Irenee Umulisa (ALMA), Frank Okey (Speak Up Africa).

Footnotes

- WHO, World Malaria Report 2025 (Dec. 2025). ↩︎

- African Union, Catalytic Framework to End HIV, TB and Eliminate Malaria in Africa by 2030 (2015). ↩︎

- Comparing malaria incidence and mortality to the 2000 baseline for 2000-2024. ↩︎

- ALMA Scorecard for Accountability and Action, Q4 2025. ↩︎

- WHO, Interventions Recommendations for Large-scale Deployment, MAGICApp (2023). ↩︎

- The Alliance for Malaria Prevention, Net Mapping Project (Q1-Q3 2025), https://netmappingproject.allianceformalariaprevention.com/ (as of 2 December 2025). Additional analysis conducted by the ALMA Secretariat. ↩︎

- The Gambia and Guinea-Bissau have also been approved by GAVI to introduce the vaccine. ↩︎

- For children under the age of 5. ↩︎

- UNICEF, Immunization Market Dashboard (as of 2 December 2025). ↩︎

- WHO, World Malaria Report 2025; RBM Partnership to End Malaria. ↩︎

- Prior to 2025, funding for malaria interventions was already under significant stress (e.g., more than half of the activities in national malaria strategic plans were unfunded, countries faced the higher cost of next-generation commodities). ↩︎

- PMI had planned to support 45 million ITNs, 70 million ACTs, 100 million RDTs, and SMC for 8 million children were planned in 2025. ↩︎

- Accounting for 4-to-1 match by the US Government. ↩︎

- African Development Bank & UNHCR, Investing in Development Responses to Forced Displacement in Africa (Sept. 2025). The number of displaced people has increased by 405% since 2009. ↩︎

- AU, African Union Roadmap to 2030 & Beyond: Sustaining the AIDS Response, Ensuring Systems Strengthening and Health Security for the Development of Africa (Feb. 2025), https://au.int/en/documents/20250319/african-unions-roadmap-2030. ↩︎

- These priorities elaborate on the objectives of the Catalytic Framework and AU Roadmap, as well as existing Member States’ commitments made via the continent-wide “Zero Malaria Starts with Me!” campaign, and other declarations. ↩︎

- E.g., Agenda 2063, Africa Health Strategy 2016-2030, Abuja Declaration’s 15% target on domestic financing for health, Catalytic Framework to End AIDS, TB and Eliminate Malaria in Africa by 2030, Yaoundé Declaration on Malaria. ↩︎

- African Union, Roadmap to 2030 & Beyond at 15 (Mar. 2025), https://au.int/en/documents/20250319/african-unions-roadmap-2030. ↩︎

- Assembly/AU/Dec.904(XXXVIII) ↩︎

- Change the Story: The Path to Zero (Feb. 2025), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3YYg9hm6TM. ↩︎

- WHO AFRO, Resolution AFR/RC75/R2, Document AFR/RC75/8 (Aug. 2025). ↩︎

- Africa CDC, Africa’s Health Financing in a New Era (Apr. 2025), https://africacdc.org/news-item/africas-health-financing-in-a-new-era-april-2025/. ↩︎

- H.E. Muhammed B.S. Jallow, Vice President of the Republic of the Gambia, also participated in the discussion, which was moderated by the Rt. Hon. Helen Clark, chair of the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health and former prime minister of New Zealand. ↩︎

- Cote d’Ivoire, Morocco, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe pledged a combined $36.6 million. The Global Fund, Pledges at the Global Fund’s Eighth Replenishment Summit (Nov. 2025), https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/quro4ogq/core_eighth-replenishment-pledges_list_en.pdf. ↩︎

- African Union, Decision on the Africa Malaria Progress Report, Assembly/AU/Dec.904(XXXVIII) (Feb. 2025). ↩︎

- WHO, MagicAPP (2025). ↩︎

- WHO, Strategy to Respond to Antimalarial Drug Resistance in Africa (Nov. 2022), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060265. ↩︎

- WHO, Malaria Vaccine Dashboard, https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZmZjN2RkOGYtYzM4NS00MWYxLThhYmMtYzg3YjMwYjU2ZDA4IiwidCI6ImY2MTBjMGI3LWJkMjQtNGIzOS04MTBiLTNkYzI4MGFmYjU5MCIsImMiOjh9 (as of 2 Dec. 2025). ↩︎

- Angola, Burundi, Burkina Faso, Congo, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Malawi, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Zambia. Additionally, Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana, Senegal and Rwanda linked their NTD scorecard with DHIS2. ↩︎

- Burkina Faso, Burundi, Congo, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania and Zambia. ↩︎